Introduction

On the afternoon of Thursday 30th June 2022, the Bristol Poverty Institute (BPI) brought together friends, colleagues and associates from a range of organisations to showcase, celebrate and explore poverty-relevant research at the University of Bristol and beyond at a Showcase Event held at the Bristol Hotel in central Bristol. This event explored a range of topics including global poverty, the cost-of-living-crisis, decolonising development, multidimensional poverty, (il)licit livelihoods and drugs policies, and social, digital and cultural lives of minoritized older adults. It also highlighted research taking place in a wide range of geographical contexts, from local analyses in Bristol to projects in Somali/Somaliland and Bangladesh, a wider project across several African countries, and poverty on a global scale. The delegate pack – including speaker biographies and talk abstracts – is available on the BPI website, along with slide decks from the presentations and pdfs of the posters displayed at the Showcase.

The event began with an introductory talk from Professor Agnes Nairn, Pro-Vice Chancellor for Global Engagement and Professor of Management, providing a brief introduction to the University of Bristol and our strengths in poverty-relevant research. She also introduced the University’s new Bristol Hub for Gambling Harms Research, which she co-leads. Over the next five years this multidisciplinary Research Centre will seek to build greater understanding and evidence around the growing and diverse impact of gambling harms across Great Britain, drawing upon expertise from a wide range of academics across the University as well as local, national and international collaborators. Agnes provided an overview of the programme for the Showcase, and introduced our fantastic cohort of speakers.

Bottom row: Mr Jamie Evans, Professor Eric Herring, Professor Phil Taylor

Ending World Poverty

We then moved on to a presentation from the founder and Director of the Bristol Poverty Institute, Professor David Gordon, who gave a thought-provoking presentation on Ending World Poverty. David highlighted how evidenced-informed policies will be key to tackling worrying, and escalating, levels of poverty, particularly in the wake of the pandemic. He then shared some staggering statistics on the pandemic, including estimates that COVID has caused around 20million excess deaths and significantly damaged both national and global economies and disproportionally impacted those in poverty. David warned that all of the gains that have been made to tackle extreme poverty in recent decades will have been reversed if current trends continue, noting how pandemics have always done greater harm to the poor and vulnerable. For example, food insecurity in the UK has now doubled since 2018 and is continuing to increase rapidly, and 1 in 5 children are now living in households where people are going hungry. He then went on to outline the ‘Bristol method’ of measuring poverty through multidimensional analysis, highlighting that we will need to better understand the extent and nature of poverty in each country to inform effective policy. He emphasised how poverty is caused primarily by structural factors not by individual behaviour, and ended with a quote from Thomas Paine from 1791 which outlined what we ought to seek to achieve through effective policy and practice.

The slides from this presentation are available via this link.

Posters

David’s presentation was followed by a break, where participants were encouraged to engage with the three posters which were on display in the refreshments space:

- A ‘Poverty-free Model Village’- A pilot project addressing multidimensional poverty in rural Bangladesh, Dr Rabeya Khatoon, Khalil Ahmed, Md. Mizanur Rahman, Md. Shafiqur Rashid, Asim Kumar Sarker and Fatema Ruhee

- (Il)licit livelihoods in Africa: Drug policy and reproduction of poverty, Dr Lala Ireland, Dr Clemence Rusenga and Dr Gernot Klantschnig

- Researching with communities at the margins: Exploring lived experiences of social, digital and cultural participation with minoritized older adults, Dr Helen Manchester, Prof. Kirsten Cater, Dr Tot Foster, Dr Paul Clarke, Dr Kirsty Sedgman, Dr Tim Senior, Dr Stuart Gray and Dr Alice Willatt

A pdf of each poster is available to view on the BPI website.

Tackling the cost of living crisis for low-income UK households

Following the break we recommenced with a joint presentation on the cost of living crisis and the ‘poverty premium’ from Ms Sara Davies and Mr Jamie Evans, who are researchers based in the Personal Finance Research Centre in the School for Geographical Sciences. Jamie kicked things off, highlighting how the number of households in serious difficulties has increased significantly in the last year or so, with over half of households reporting that their finances are worse than they were pre-pandemic. He reported that some groups are more effected than others, with groups such as low-income earners, social renters, single parents, household with disabled person(s) and larger families all more affected than others. Jamie then went on to introduce the key concept of the ‘poverty premium’, whereby the poor are effectively paying more for essential services including food and utilities.

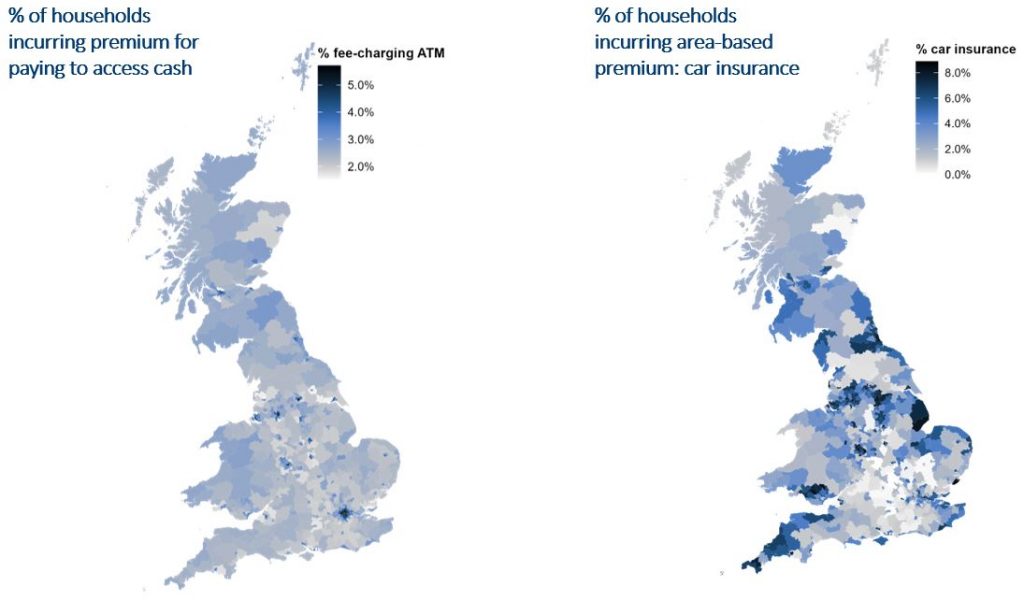

This led onto Sara’s portion of the presentation, which delved into the poverty premium in more detail. She highlighted how many of the suggested solutions to tackling the cost of living crisis weren’t necessarily appropriate for those in poverty. For example, the advice to “shop around” is not practical for those reliant on public transport or accessing supermarkets by foot, and they also do not have the financial flexibility to buy in bulk to save money overall. Sara noted how the market is also penalising people for making the choices which are necessary for them, such as choosing to ‘pay upon receipt’ for their utility bills rather than setting up a direct debit, or taking out payday loans or a high-interest credit card to cover immediate costs. She therefore highlighted how structural circumstances has a bigger impact than choice, and indeed how people do not always have access to that choice anyway. For example, pre-payment meters for electricity, which are more common in lower income homes, are actually more expensive with a higher standing charge than other electricity meters, so even with minimal use bills can be unaffordable. Sara therefore summarised that the poverty premium represents a mismatch between the needs and circumstances of low-income households and the markets that serve them. She additionally highlighted how there are big regional differences in how poverty premiums are incurred, which in many ways reflects the geographical distribution of poverty. Examples included the fact that fee-paying ATMs are more common in poorer areas than wealthier ones, and the fact that car insurance premiums tend to be higher in deprived rural areas. and She therefore concluded by sharing her hope that there would be impetus and opportunity through the government’s ‘Levelling Up’ agenda to address some of these inequalities.

The slides from this presentation are available via this link.

Decolonising Development: Academics, Practitioners and Collaboration

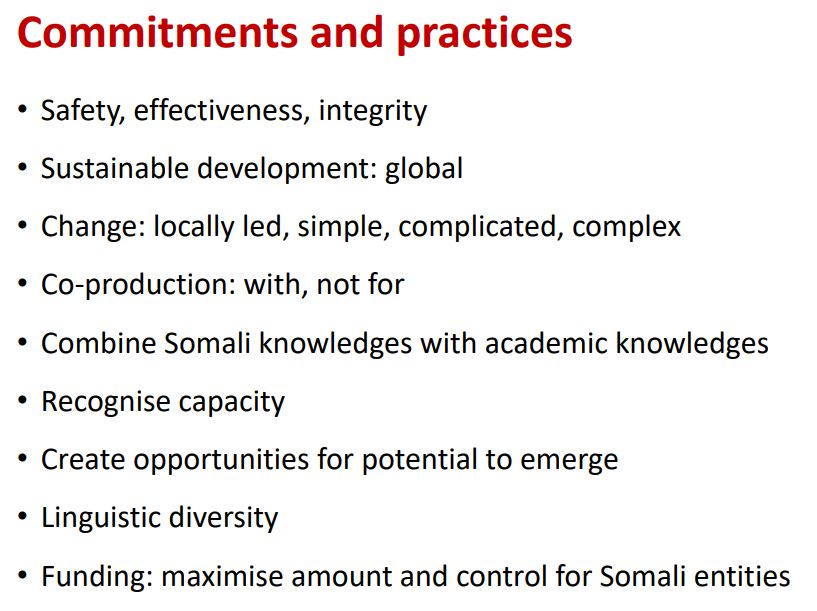

The final presentation came from Professor Eric Herring, a Professor of World Politics in the School for Sociology, Politics and International Studies (SPAIS). This talk was entitled Decolonising Development and explored how academics and practitioners around the world can collaborate in an equitable way, identifying and challenges some of the colonial legacies in development research. Eric framed this talk in the context of his own journey into collaborative work with partners in Somali and Somaliland, which are effectively separate entities but technically one country and is therefore particularly complex. He highlighted how this is one of the poorest countries in the world which is currently experiencing an enormous humanitarian emergency, with around half of its population needing urgent assistance right now and high potential for widespread famine. Eric introduced how bow Somali and Somaliland are pioneers in ‘mobile money’, which has replaced formal banking in the region with even relatively poor people using mobile phones for their money management. He revealed that the global aid industry has, surprisingly, never engaged with these companies despite their great success, not only persisting through challenging times including civil war and operating effectively in a complex clan-based society, but also managing to be an equal opportunities employer. Eric has therefore been trying to connect the companies and local researchers who work with them with people who may learn from them, but has encountered several challenges along the way. This includes, for example, the fact that many academics in Somali/Somaliland do not have PhDs or publish in peer-reviewed journals, and are therefore not seen as an appealing partner for international academics and they cannot compete with ‘powerhouse’ institutions in neighbouring countries such as Kenya and Uganda. Additional challenges include the insecurity of the region, the fact they are experiencing an extreme humanitarian emergency, huge rates of illiteracy, and a university system with next to no research capacity. He therefore highlighted how decolonising processes therefore requires a deep understand of the context and how to operate there. He went on to provide a case study from his own work with Somali First – a joint initiative between Somali social enterprise Transparency Solutions and the University of Bristol – which promotes Somali-led development. He expressed gratitude to the University of Bristol for being willing to take a risk and get behind this initiative from the early stages and agreeing to a formalised strategic partnership. Eric concluded by highlighting the fact that practices and perceptions from the colonial period are still embedded in a lot of development work – including in the use of colonial languages such as English in research – and that identifying colonial legacies and actually doing things differently will be key to achieving positive change with a renewed focus on co-production.

The slides from this presentation are available via this link.

Closing remarks

The Bristol Poverty Institute Showcase was brought to completion with closing remarks from the Pro-Vice Chancellor for Research and Enterprise Professor Phil Taylor. He provided a summary of the talks and posters presented at the Showcase, and also reflected on some other topical issues around poverty in his own field. In particular, he noted that there are an estimated 6.5million people in the UK currently in fuel poverty, and with the upcoming further price cap rise in the autumn this is only going to get worse. Phil therefore outlined ambitions to work with the Bristol Poverty Institute and external partners on tackling issues at the nexus between health, climate change and fuel poverty. In closing the event Phil thanked the speakers, poster authors, organisers and attendees for their fantastic contributions to the showcase event, and encouraged everyone to stick around and continue the conversation at the drinks reception.

Thank you to everyone who attended and participated in our first in-person event in over two years – we hope you enjoyed it, and that we get to meet again soon!

The presentation slides, speaker biographies and abstracts, and pdfs of the posters are all available on the BPI website.