As we welcome in 2024, the BPI team are reflecting on the challenges, successes and opportunities we have experienced through 2023, and looking ahead to the coming year and beyond. Join us for a whistle stop tour of a few of the highlights in this blog post! If you want to keep up to date on activities and opportunities across the Institute, do make sure you sign up to our monthly newsletter via this page and/or email the BPI team to sign up to our main mailing list.

January

In January 2023, the BPI’s main focus was on producing and submitting a bid to the internal Strategic Research Investment Fund (SRIF). With input from the BPI Advisory Board, the BPI Manager Dr Lauren Winch put together a strong bid with a number of work packages, and we were delighted when funding for all work packages was confirmed in March. Funding has been secured for a range of activities up to July 2025, which includes new posts within the team, an exciting new interdisciplinary seedcorn fund, and a BPI conference in 2024.

February

On 12th February we were delighted to welcome Dr Nkechi S.Owoo to Bristol as a Bristol ‘Next Generation’ Visiting Researcher. Dr Nkechi, a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Economics at the University of Ghana, spent six weeks working with the BPI Director, Professor David Gordon on the effects of climate change on health outcomes. Nkechi is one of Africa’s foremost young scholars, and her research focuses on spatial econometrics in addition to microeconomic issues in developing countries, including household behaviour, health, poverty and inequality, gender issues, population and demographic economics, as well as environmental sustainability.

March

Some of our activities in the first part of the year were significantly impacted by strike action across the University sector. This included plans for a cross-sector event on Housing, ‘Home’ and Poverty scheduled for 15th March, which had to be postponed until May. We did, however, deliver a fantastic event in collaboration with the South West International Development Network (SWIDN) to celebrate International Women’s Day on the 8th March, chaired and facilitated by BPI Board Member Dr Tigist Grieve. At this collaborative online event entitled ‘From Menarche to Menopause‘ we heard from several expert speakers from the academic and not-for-profit communities about their work and research related to menarche, menstruation, menopause and mental health worldwide. Together the event explored issues affecting women and girls and discussed what we can do as a wider community to tackle these issues. More information is available on the event page.

Dr Nkechi Owoo also continued her work with the BPI in March, before returning home to Ghana. This included an engaging hybrid seminar on ‘The Effects of Climate Change on Health Outcomes in Ghana’. A recording of the seminar along with more information is available in the events resources section of our website.

March was a particularly busy month for the BPI Director, Professor David Gordon, who travelled to Sweden after Nkechi’s departure to work on an evaluation of the AgeCap programme in Sweden, and then chaired an all-day meeting for the Academy of Finland the following week.

April

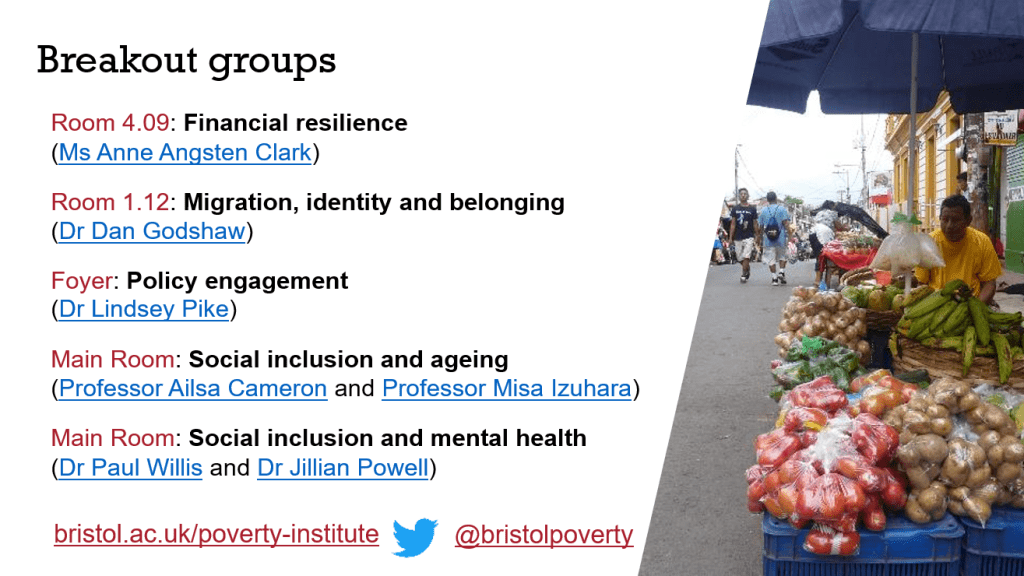

In April, we teamed up with the University of Bristol’s Health Psychology and Interventions Group (HPIG) for an afternoon of thought-provoking discussion at a cross-sector workshop. Entitled “Don’t Be Poor”: Collaborative approaches to health behaviour change interventions, this workshop was aimed at those wishing to explore the real-world context of health interventions and how we can better bring together our skills and collaborate across disciplines when designing interventions and conducting healthcare research to bring tangible benefits to those most in need. We were really pleased that the event attracted a wide range of attendees from across different sectors, with some really positive takeaways including an enhanced awareness and understanding of dimensions of poverty and vulnerability which can intersect with health behaviours.

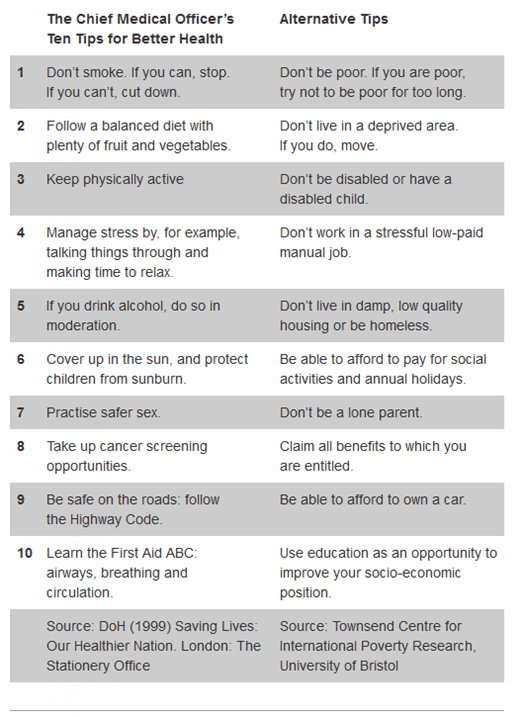

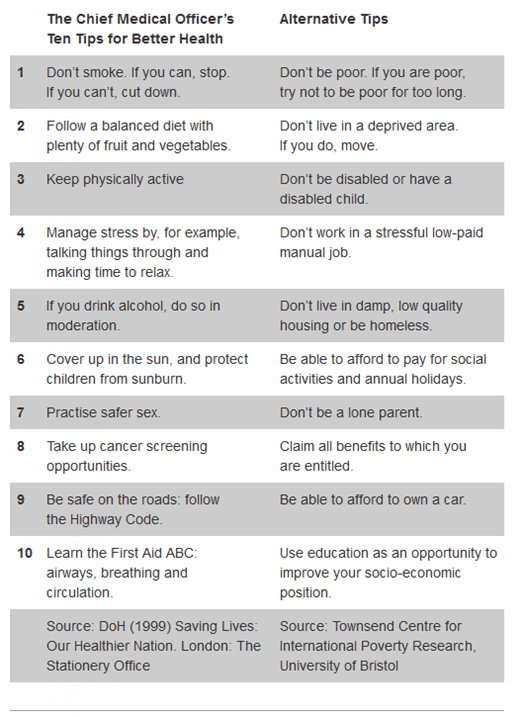

The title of this event was inspired by some work undertaken by Professor David Gordon and colleagues over twenty years ago. This was inspired by some ‘top tips’ for better health from the Chief Medical Officer as part of the Government’s published response to the Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health report. These ‘top tips’, whilst valid in themselves, neglected to really address the causes or potential solutions to health inequalities. This therefore prompted a somewhat satirical response from Professor Gordon and his colleagues which highlighted the kinds of policies which would be needed to actually reduce health inequalities in the UK. One of their key ‘tips’ for better health was simply: “Don’t be poor”. It seems these lessons may still need to be learnt.

May

May was another really busy month for the BPI, with a range of events and high-level meetings. This included, for example, successfully delivering our half-day multi-sector event on Housing, ‘Home’ and Poverty, feeding into the new GW4 strategy, meeting with members of the Global Coalition to End Child Poverty to outline collaborative work on climate change and child poverty, and convening a meeting for the Directors of all seven of the University of Bristol’s Specialist Research Institutes.

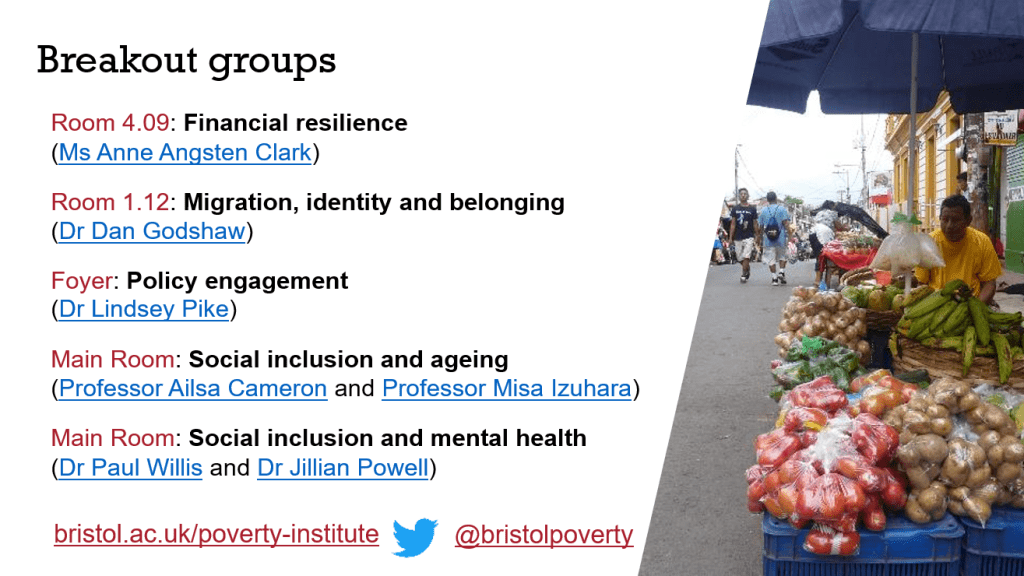

The Housing, ‘Home’ and Poverty event was a real highlight, bringing together representatives from different sectors and backgrounds to explore the intersections between poverty and elements of housing, the concept of ‘home’, and other related issues. The event included presentations, breakout sessions, a powerful testimony on the experience of these issues in conjunction with living with disabilities, and networking opportunities. Presentations from the event can be downloaded from our event resources page, and you can also find out more about the event itself in our blog post.

June

In June we welcomed Dr Tanveer Naveed from the University of Gujrat in Pakistan who also came to Bristol via a Bristol ‘Next Generation’ Visiting Researcher award, the same scheme which funded Nkechi’s visit earlier in the year. Tanveer’s research interests and contributions focus on measuring valid and reliable education, assets, health and human development indices, and developing scientifically rigorous measures for multidimensional poverty and child poverty that are applicable in low- and middle-income countries. During his visit, Tanveer collaborated with the Professor David Gordon on multidimensional poverty measurement, particularly in Pakistan.

June also saw the publication of a fantastic new book on Decolonizing Education for Sustainable Futures from BPI Advisory Board Member Professor Leon Tikly, along with Bristol academics Dr Artemio Cortez Ochoa, Professor Julia Paulson and Warwick’s Professor Yvette Hutchison. This book explores the link between sustainable futures and decolonized education, offering theoretical and practical insights on creating decolonized futures through innovative approaches and reparative justice in education.

July

Our visiting researcher from University of Gujrat, Dr Tanveer Naveed, gave two fantastic seminars in July. The first was on The Construction of Household-based Asset Index: Measurement of Economic Disparities in Pakistan by using MICS Micro-data, and the second on The Estimation of Human Development Index at Household Level and Estimation of Human Development Disparities in Pakistan. Resources from both seminars can be found on the BPI website.

We also had some changes in the BPI team in July. We bid farewell to our long-standing Senior Administrator Joe Gillett, who was moving on to undertake some research of his own building on his PhD research. We also said goodbye to Katherine Fitzpatrick, who had come in on a fixed-term contract to help us out with some packages of work. Both will be very missed from the team, but we were delighted to welcome Tracey Jarvis as our new permanent Senior Administrator taking over from Joe. Tracey got up to speed really quickly, and has been a fantastic asset to the team.

August

August is always a quieter month in terms of events and meetings, as many people take a break over the summer. It was still a busy month for the BPI team, though, developing plans for the upcoming autumn term and launching recruitment for our new BPI Development Associate who will lead on our new Seedcorn Fund in 2024.

September

September saw a wave of high-profile events for the BPI in collaboration with colleagues including UNICEF and the New School in the USA. Our largest activity was a side event at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Science Summit, hosted at UNICEF’s Head Office in New York on the topic of Advanced Tools for Analysing Poverty, Climate and Environmental Changes. Chaired and co-designed by the BPI Director, Professor David Gordon, this event brought together researchers engaged in novel approaches to develop measures, monitoring, and understanding for both the causes and the consequences of poverty. Despite many decades of progress, hundreds of millions of people still live in extreme poverty. Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, economic and political turmoil, armed conflicts, and environmental challenges do not only threaten to halt recent improvements but reverse many of the gains in poverty reduction. Whilst numbers in the room were limited, the session attracted hundreds of attendees from all around the world on the live stream.

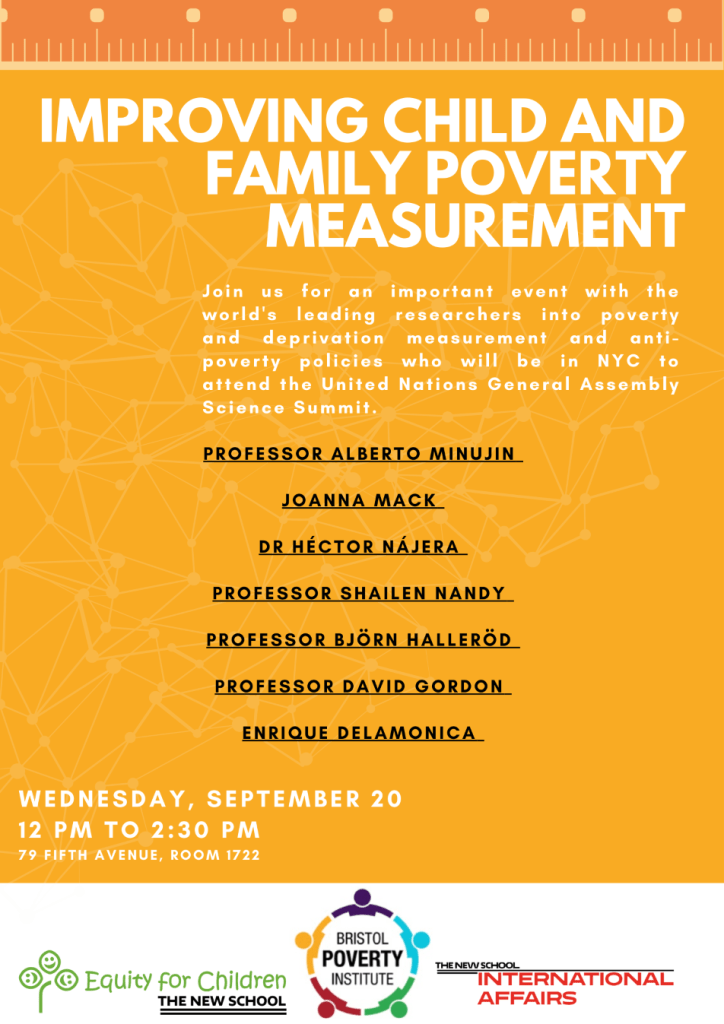

Following on from this, we were also involved in a parallel event hosted by the New School on Improving Child and Family Poverty Measurement which brought together some of the world’s leading researchers into poverty and deprivation measurement and anti-poverty policies who had travelled to New York for the UNGA Science Summit.

October

October saw the new academic year getting into full swing, and we held a really nice, informal ‘Meet the BPI’ event on campus. The aim of the event was to give both academics and Professional Services colleagues from our University the opportunity to meet the BPI team, find out what we do, learn more about the support and engagement opportunities available through the BPI, and mingle with like-minded colleagues over a cuppa. We had a really good turn out, and it was a great opportunity to catch-up with familiar faces and meet some new ones and identify some potential new synergies and spaces for engagement and collaboration.

The 17th October every year is the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty (IDEP), and each year the Global Coalition to End Child Poverty – which we are an active member of – plan activities to coincide with this. Last year we published a policy briefing on Ending Child Poverty: A Policy Agenda, and this year we launched a Call to Action for Governments to expand social protection and care systems and promote decent work to address child poverty. This Call to Action was developed jointly by UNICEF, Save the Children, Young Lives, Arigatou and the Bristol Poverty Institute, and was officially launched at a live online event on IDEP itself. Find out more in our news story.

November

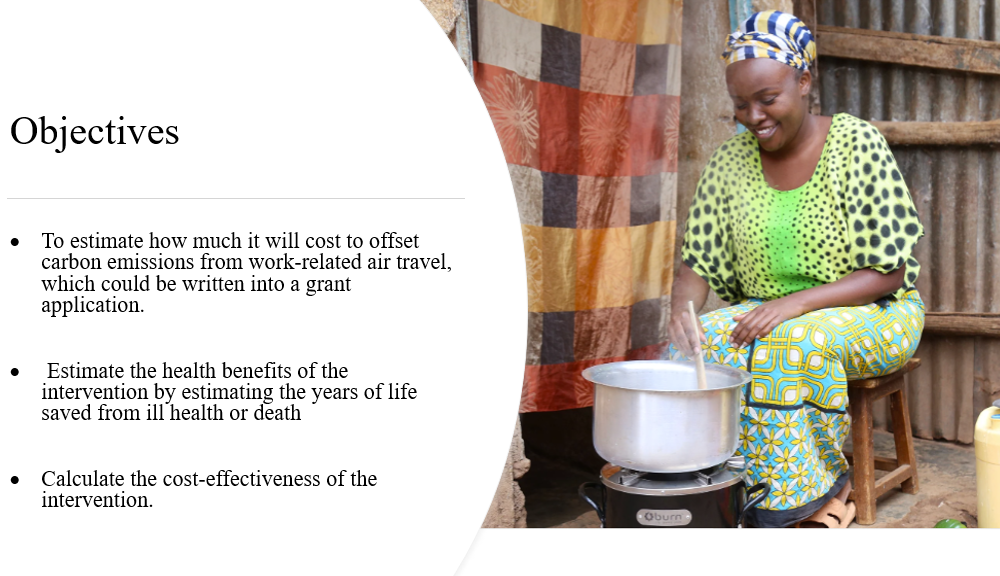

November was our busiest month of the year for events, with a packed schedule including a hybrid seminar, a co-hosted conference session, and an interdisciplinary forum. We kicked off the month with our hybrid event exploring Towards Net Zero and Tackling Poverty, where we introduced findings from our Travel Carbon Project which was undertaken by Professor David Gordon and one of his PhD students who is already a qualified medical doctor, Dr Cynthia Fonta. Their aim was to calculate both the costs and years of life which could be saved by carbon offsetting the University’s work-related emissions through funding clean cooking stoves and/or potable water provision in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. They shared their findings and the potential implications with a hybrid audience at this event, alongside an engaging presentation from Dr Sam Williamson, who is doing work on sustainability and cooking in a range of contexts including Nepal, Sierra Leone and Uganda.

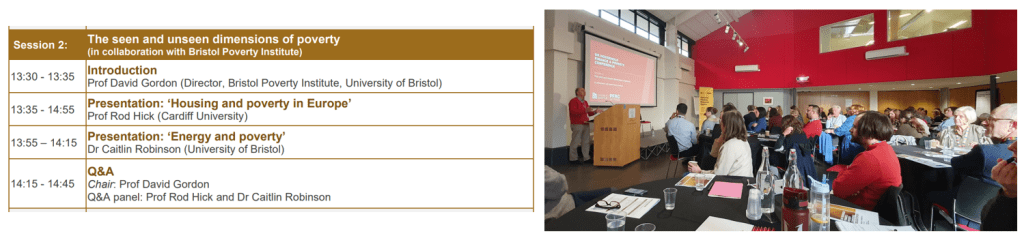

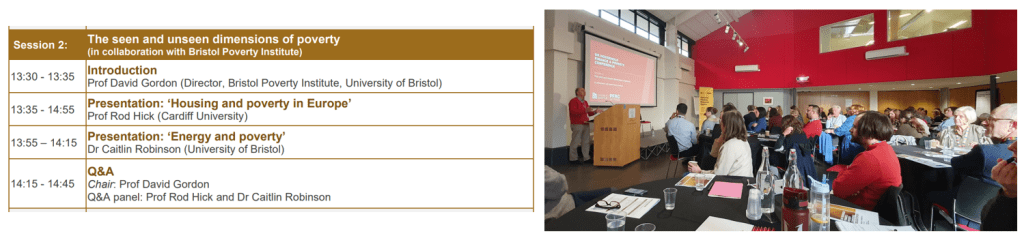

The following week, we co-hosted a session on The Seen and Unseen Dimensions of Poverty at the fantastic Personal Finance Research Centre (PFRC) anniversary conference. This well-organised and well-attended event was celebrating 25 years of the PFRC, which applies multi-method approaches with specialisms drawn from social policy, human geography, psychology, and social research to explore the financial issues that affect individuals and households under the leadership of BPI Board Member Professor Sharon Collard.

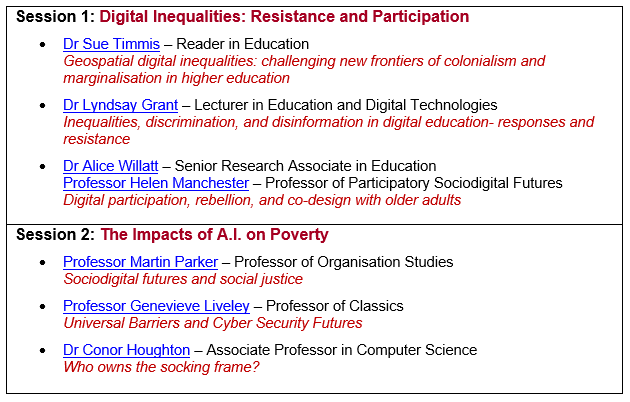

A final highlight was our interdisciplinary forum on Poverty and Social Justice in a Digital Future, which consisted of two thematic sessions exploring digital inequalities and the impacts of AI on poverty. The aim of this event was to build up internal awareness and offer researchers from different communities to identify synergies, with a view to being better placed to collaborate in response to future funding calls and to situate considerations of poverty and social justice within the mindsets of researchers working in the digital space for these future bids. We actively encouraged participation from researchers who weren’t currently working directly on poverty or poverty-related issues, and from all corners of the University. We had a fantastic panel of speakers from across Arts, Social Sciences, and Engineering, who gave us wide-ranging, engaging talks on new frontiers of colonialism and marginalisation, discrimination and disinformation, participatory research methods, sociodigital futures and social justice, cyber security, and machine learning and AI.

December

As 2023 drew to a close, there were lots of exciting things still happening at the BPI. We were delighted to welcome Joe Jezewski to join our team as our new BPI Development Associate, as well as four new academics to our BPI Advisory Board bringing more diversity and expertise to our already strong Advisory Board. Our new Board members are:

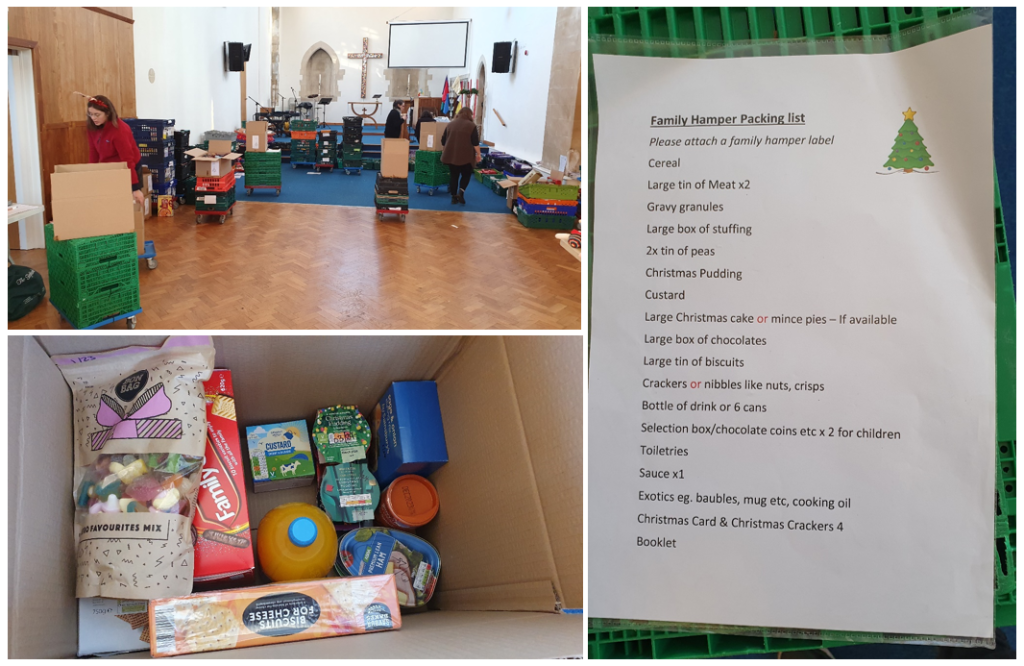

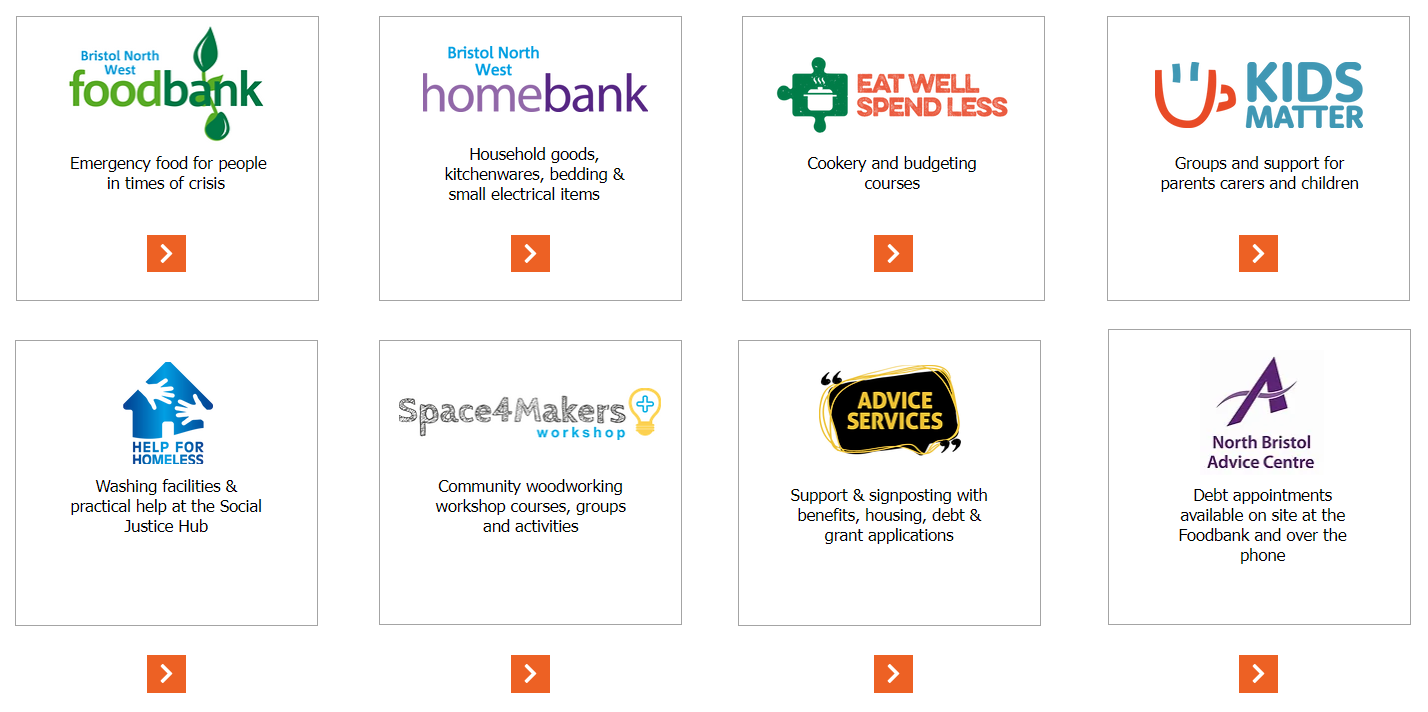

In other news, the BPI Director travelled to Thailand to work with the Thai government and UNICEF on poverty measurement for the country. Closer to home, members of the BPI team rolled up their sleeves to bake cakes and cookies to raise money for the North Bristol and South Gloucestershire foodbank, where some of the BPI team and colleagues spent a rewarding day volunteering on 21st December. You can find out more about our experience, including some information about the foodbank and tips for donating, in our blog post.

Looking ahead

So, it has been another busy year for the BPI, and we’re really excited to have lots of exciting things in the pipeline, including our new interdisciplinary seedcorn fund launching imminently, collaborations with a range of local, national and international partners, and a wide range of events. We’ve got our rescheduled event on gambling, poverty and marginalisation, as well as new events in development including a seminar on underemployment and Universal Credit, a participatory research methods workshop, training on achieving impact for poverty-relevant research, a seminar on socially just future cities, a food justice mingle, to name just some of them! Of course, we will also have our 2024 conference! This will be taking place across two days in June, with a focus on Poverty and Social Justice in a Post-COVID World. The first day will be an in-person event in Bristol with a UK focus, and the second day will be online with an international audience and focus. We’re aiming to have sessions across a wide range of topics including mental health, finance, and education among others, and will try and make sure there are sessions available to people in different time zones around the world. We’ve just recruited a new member of our team to help with planning and delivery of this conference, who will be joining us later this month – more info soon!

To keep up to date with the BPI’s plans you can sign up to our mailing list, subscribe to our monthly newsletter, check out our website, and/or follow us X/Twitter. You can also get in touch with the BPI team via bristol-poverty-institute@bristol.ac.uk– we’d love to hear from you!