Introduction

On Thursday 11 February, the Bristol Poverty Institute (BPI) held the fourth webinar in our ‘Poverty Dimensions of COVID-19’ series: Poverty Dimensions of COVID-19 for Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs)

The webinar had over 60 attendees representing a range of sectors and organisations including civil sector, national and international NGOs, charities, consultants, and academics from around the world, including individuals from France, Mexico, Canada, Senegal, Indonesia, Norway, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, Argentina, Turkey and China. This diverse audience was deliberate: the series has been designed to bring together a variety of participants representing different sectors, with a range of theoretical, methodological, and disciplinary approaches.

Our webinar featured four fantastic speakers who explored different dimensions of the impact COVID-19 has had on girls in LMICs from different perspectives, with a Q&A session at the end. The slides from these presentations will be available shortly on the BPI website, and we will also be uploading recordings of the presentations.

Dr Tigist Grieve and Dr Alba Lanau Sánchez, ‘Corona has really spoiled a lot of things’: Adolescent girls experiences of COVID in Burkina Faso & Sierra Leone

Our first presentation came from two collaborative speakers: Dr Tigist Grieve, Senior Research Associate at the University of Bristol; and Dr Alba Lanau Sánchez, Research Fellow at the Centre d’Estudis Demogràfics (CET) which is an affiliated institute to the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in Spain.

Tigist began by providing an outline of the African Report on Child Wellbeing 2020, produced by the African Child Policy Forum (ACPF) in collaboration with partners including the University of Bristol and researchers across the five countries where the research took place. In response to the emergence of COVID-19 the project team are seeking to explore what the economic impact of the pandemic has been on adolescent girls, and to what extend the impacts of the pandemic have been mediated by factors such as girls’ socio-economic status and geographical location.

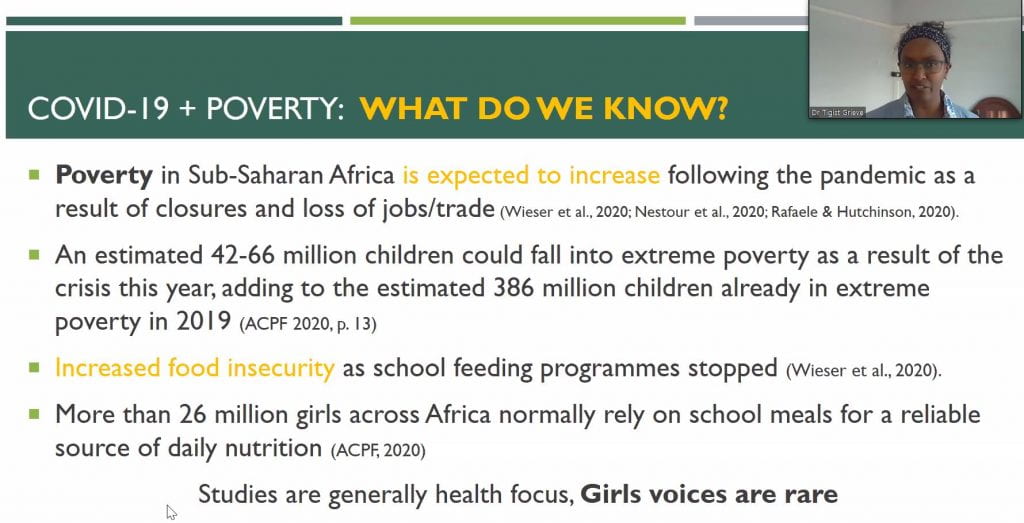

This presentation focussed primarily on impacts in Burkina Faso and Sierra Leone. Tigist explained how the situation girls in each country is different. For example, Burkina Faso have prioritized improving young people’s access to health care though its National Health Development Plan, whilst in Sierra Leone they abolished secondary school fees and focused on the National Reproductive, New-born, Child, and Adolescent Health Strategy. The countries at the focus of the research have relatively low figures of COVID-19 in terms of deaths; however, there is major concern over adolescent girls. Tigist explained that poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa is already a huge problem, and one which is likely to worsen. There is major concern about the risks to children because of increased food insecurity, with more than 26 million girls across Africa already relying on school meals as a source of nutrition. Access to school feeding programs have been stopped due to schools being closed, significantly impacting on the lives of huge numbers of children and young people.

Alba then introduced some of the findings of their project to date. She began by explaining how whilst most research studies are generally focussed on health this project specifically sought to draw upon girls’ voices, which are rarely heard. The study involved talking to 87 adolescent girls aged 14-19 across five countries. Girls were asked about their education, safety, health, hopes and dreams and specifically their own understanding and experiences of COVID-19. Alba explained that the general expectation is already for an increase in poverty and inequality in Africa; however, the team wanted to find out how COVID-19 has reinforced this, and how it has affected girls’ experiences.

Alba highlighted that girls have different experiences depending on their positionality, and the team identified three different groups (plus an additional group only in Burkina Faso). The groups were

- Those with limited economic impact.

- Those who are managing to cope.

- Those who are struggling and/or have been severely impacted.

- Those whose lives are defined by conflict (Burkina Faso only).

Alba explained that the first group are relatively sheltered from the economic impact of pandemic. The second group have experienced some loss in livelihood and income but are coping and adapting by using their existing resources. In this group more girls are now working in their family workplace. The third group are those struggling and suffering severe impact, including extreme poverty and hunger and complete loss of income. Many girls in this group reported impacts on others rather than themselves, talking about their friends/family members losing income and having to care for others. Some girls also reported others who were struggling and turning to sex work. For those in the fourth group (Burkina Faso only) conflict is still the key factor in their lives, and COVID-19 has therefore not altered their lives. Alba noted that within this group those who have money had sent their children away, whereas those without money were forced to remain in the conflict situation. This is therefore an example of how experience of the pandemic is mediated by socio-economic and geographic position, and those better off are often more protected.

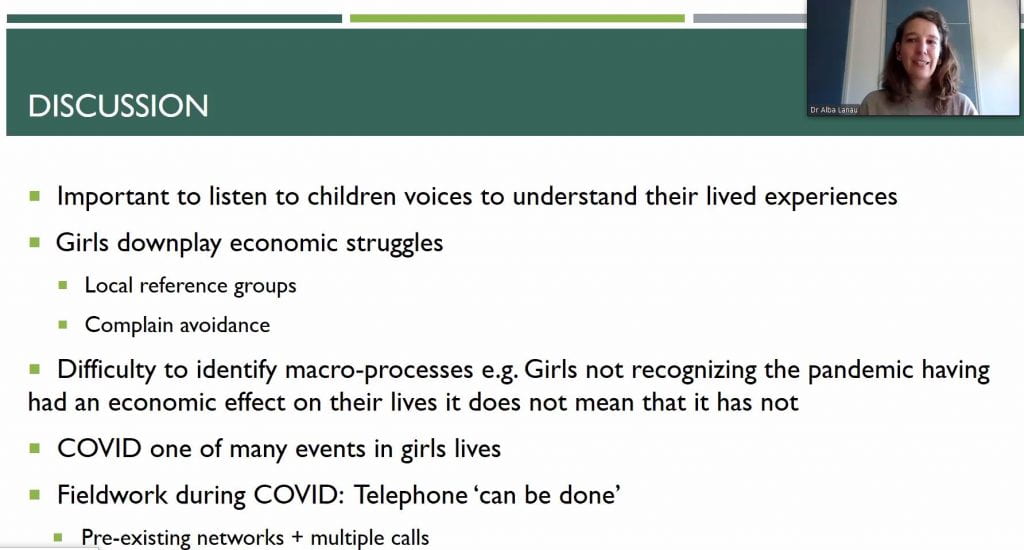

Alba highlighted how important it is to listen to children’s voices to understand their lived experiences, particularly girls, who often downplay economic struggles. The girls interviewed through this project commonly reported isolation, fear of COVID-19, and feelings of insecurity, with one interviewee stating that “early marriage is when you are sent to marriage at an early age due to poverty”.

Alba and Tigist concluded by highlighting that the pandemic will increase economic inequality, hitting the poorest the hardest. Income support is therefore needed for those working in informal sectors, small farms, and other small businesses. The pandemic is likely to deviate transitional trajectories accelerating the end of schooling and/or marriage and increasing gender inequality. They therefore called for responses to the (post) pandemic to be gender sensitive.

Ms Maria McLaughlin, The Case for Holistic Investment in Girls: Improving Lives, Realizing Potential, Benefitting Everyone

The next speaker was Maria McLaughlin, Global Policy and Advocacy Advisor for Economic Empowerment at Plan International with a focus on adolescents and youth. Maria is also a researcher on women and youth empowerment, with a focus on market entry-points for women and youth, and analysis of their barriers to entry and success. Plan International is an independent development and humanitarian organisation that advances children’s rights and equality for girls.

Maria introduced a study undertaken by Plan International and Citi bank during late 2019 and completed in 2020. The study looked at the case for holistic investment in girls, specifically adolescent girls. She explained that this study is based on some assumptions on the pathway through adolescence for girls and how it compares with the situation for adolescent boys. The assumptions made in this study is based on information from various analyses, including from the Gates Foundation, focusing on ages 10-19 which is a critical phase in life for both girls and boys when many transitional social, economic, and biological events are taking place.

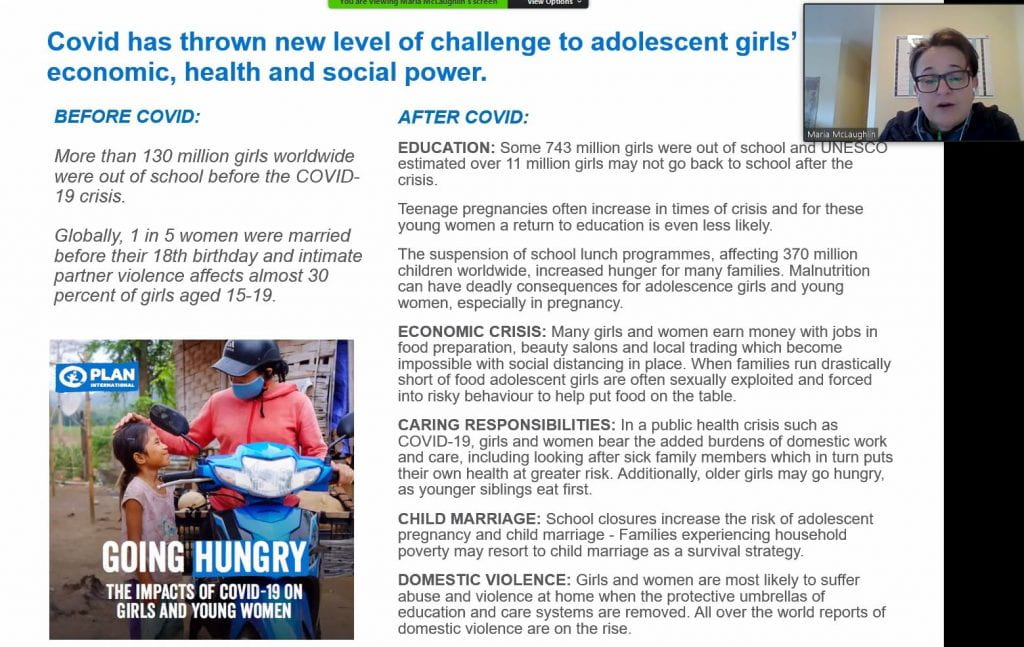

Maria explained that challenges faced by girls in LMICs include early and forced marriage, with 21% married before their eighteenth birthday. She went on to introduce some key pre-COVID-19 statistics, which showed that:

- 132 million girls worldwide are out of school, including 100 million girls at secondary school age.

- More than 85% of girls in low-income countries do not complete secondary school.

- Intimate partner violence affects around 29% of girls aged 15-19 worldwide.

- Globally one in five women were married before their eighteenth birthday.

- Almost a billion girls and young women under the age of 24 are lacking key skills needed for life and work. In lower middle-income countries, this translates to 75% and rises to 93% in low-income countries.

This research was carried out in eight LMIC’s: Ghana, Uganda, Mali, El Salvador, Bolivia, India, Lao PDR, and Egypt. The team looked at potential for investment in 12 years of education through to secondary school completion and two years of multi complement intervention to prevent child marriage and violence and promote economic independence. There is an assumption that this leads to increased years of schooling, leading to higher employment earnings. The analytical framework for the research looked at the business-as-usual scenario and compared with an increase in investment scenario. Maria explained that assumptions must be made around education, labour demand, and government policies, so the research does not take these variables into account. Maria also explained that there were limitations and boundaries for this research. For example, one challenge when looking at global data was that it rarely segregates for gender and age.

With these caveats notes, Maria reported that the project findings indicated that if 100% secondary school completion were achieved and if investment of achievement were in place it could lift the emerging economies by ten percent compared with pre COVID-19. The report makes an argument that the level of investment involved – $1.30 per day – has a multiplied effect in terms of GDP as well as moral investment. She noted that the cost in Mali and Uganda would be greater than the returns; however, the positive impact there would be much greater than the other countries. She also reported that in countries where the secondary school completion rate is lower the benefits will take longer to materialise but are greater long term. Maria therefore summarised that holistic approach to investment would have a higher return over the course of a girl’s life. The report states that it is not just the education alone to achieve the benefits: a multi-level approach is required.

Maria concluded her presentation by exploring the potential impacts of COVID-19 on these groups. The emerging research speculates on the impacts of COVID-19 based on the trajectories. Before COVID-19 more than 130 million girls worldwide were out of school, one in five women were married before their eighteenth birthday, and almost 30% of girls aged 15-19 were affected by intimate partner violence. After COVID-19, 743 million girls were out of school and UNESCO estimates that over 11 million girls may not return to school after the crisis. Teenage pregnancies often increase in times of crisis, extreme poverty will be faced by many families who relied on school lunch programmes, and cases of child marriage and domestic violence are all rising. These are therefore worrying trends that need urgent attention.

Dr Anita Ghimire, the impact of COVID-19 on girls working in the adult entertainment sector in Nepal

The final speaker was Dr Anita Ghimire, Research Director at the Nepal Institute for Social and Environmental Research (NISER). Her research experiences are on migration and mobility, social norms and gender, adolescents and young people, and social protection, in addition to evaluation studies of different interventions.

Anita introduced ‘Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence’ (GAGE), a nine-year programme of work looking at research in nine LMICs to try and understand what works for enabling adolescent girls to transition into a better adulthood. In Nepal there are three different strands of GAGE, with Anita’s presentation focussing on girls working in risky jobs in the adult entertainment sector (AES). Anita explained how the AES is an informal economy, consisting of hotels, guesthouses, commercial sex work on the street and freelance sex work. This work is establishment based and affiliated with an institution such as a hotel or dance bar, and involves physical, economic, and sexual exploitation of girls, including minors. Girls enter this sector through their peer network, boyfriends, or male relatives, or recruiting mechanisms from brokers who are operating online.

Anita noted that entertainment sectors were closed in March 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic; however, informal personal connections remained, and hotels were still connecting girls with clients discreetly. There was still a decrease in work, with sex workers reporting that they previously had three to five customers a day, which dropped down to only one or two clients a week during lockdown. The Nepalese government eventually eased lockdown for a few hours per day which meant clients visited early morning and evening, although there continued to be a lower demand due to factors including changes in working hours, challenges of childcare for the women workers, worries about catching COVID-19, and closed borders preventing people from travelling from surrounding countries for adult entertainment. As a result many girls moved their work onto the streets, increasing competition for the limited clientele. This included an increase in international sex workers from China, Malaysia, and Africa who had previously worked in high-end casinos and were willing to charge lower rates, creating more competition for Nepalese girls and women.

The implications of lockdown for these women and girls were therefore severe, including an increase in food insecurity and vulnerability. Many of the girls had previously eaten their daily meals in the establishment where they worked, so were unable to eat due to their workplace being closed. Some were also living in the hotels or guesthouses where they worked, and when the establishments closed, they were also made homeless. Sometimes the girls were so desperate that they sold their bodies for a single meal or drink. Anita reported that the levels of desperation were so severe that some said they would work for a small amount of money to buy poison to kill themselves and their children, as they would rather die than be unable to feed their children.

The girls reported an increase in violence from their partners and/or clients, and some clients would not pay them money and buy them a beer instead. There was also violence from police arresting girls for just being on the streets. Some were blackmailed for sex from clients; there were threats to tell the girls families if they did not provide sex for free. There was also increased vulnerability to COVID-19 infection because of the close contact, and an increase in sexually transmitted infections and in pregnancies.

Anita went on to introduce some of the survival strategies the women and girls had implemented during lockdown. For example, some of the unmarried, child-free girls had previously made a good amount of money and were therefore able to use their savings to survive. Working for less money or for food was another strategy. Some girls tried alternative livelihoods, some cut down on food and basic hygiene, and some sold their assets. Anita then highlighted some of the other outcomes of the pandemic on girls on the AES. For example, she noted how some of the girls organised themselves into groups to help with childcare and to help one other with clients. In addition, whilst some girls started revisiting exploitative relationships with partners and employers, there was an increased recognition of the exploitation they were facing and a movement towards making decisions that were beneficial for themselves. They also learnt the value of savings and looked at alternative less risky livelihoods.

Anita concluded by highlighting the importance of activating and creating awareness on secondary reporting mechanisms and to tackle issues related to deprivation of basic human rights of children, particularly around food, shelter, and protection. Having hungry children hungry is a big problem for the girls in the AES and the social protection system should therefore expand to women working in this area.

Discussion

Following the presentations the Chair, Dr Lauren Winch (BPI Manager) opened up the floor to questions from the audience, as well as discussions among the panel members. Topics of discussion included how poverty and sex work can go hand-in-hand in many different country contexts, gender inequalities, and shifting aspirations among girls in terms of education, career and family lives.

Recordings of the discussion, as well as all of the presentations, will be available on the BPI website shortly.

Closing the discussions Lauren summarised how the webinar covered a range of interesting and important topics. She noted how COVID-19 is having wide ranging, complex, and devastating impacts on communities across the world and those in poverty will be disproportionately affected, exacerbating existing inequalities including those relating to gender. She noted that hopefully by coming together and learning about different perspectives, approaches and challenges we can be better situated to make a positive impact individually and collectively. The Bristol Poverty Institute is keen to keep these discussions going, and to explore ways to tackle the challenges and inequalities exposed and exacerbated by this pandemic. For more information or to discuss an idea please get in touch with the BPI team (bristol-poverty-institute@bristol.ac.uk).

Finally, Lauren also announced that the BPI are running a large online conference from 27-29 April 2021 exploring Poverty and the Sustainable Development Goals at all scales from the local to the global. The conference will have non-academic speakers throughout, including people with lived experiences of poverty to ensure their voices are represented. It will explore a wide range of topics, from food and nutrition to education, and from livelihoods and debt to child health and development, and the ambition is to bring together representatives from across the world to tackle these complex issues.

For more information on the BPI…

Check out our website: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/poverty-institute/

Follow us on Twitter: @bristolpoverty

Get in touch: bristol-poverty-institute@bristol.ac.uk

Authors: Mrs Melanie Tomlin and Dr Lauren Winch