This blog was written by the authors of the Unequal Pandemic: Clare Bambra (Professor of Public Health, Population Health Sciences Institute at Newcastle University); Katherine Smith (Professor of Public Health Policy at University of Strathclyde); and Julia Lynch (Professor of Political Science at University of Pennsylvania). It was originally posted on the blog Transforming Society and has been re-posted here with their kind permission.

In 1931 Edgar Sydenstricker identified inequalities in the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic, reporting a significantly higher incidence among the working classes. This challenged the widely held popular, political and scientific consensus of the time that ‘the flu hit the rich and the poor alike’.

In the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, there have been parallel claims made by politicians and the media – that we are ‘all in it together’ and that the COVID-19 virus ‘does not discriminate’.

But we can dispel this emerging myth of COVID-19 as an ‘equality of opportunity’ disease, by showing how, just as 100 years ago, the pandemic is experienced unequally across society. COVID-19 and inequality are a syndemic – a perfect storm.

Our new book delves into international data and accounts, reaching the conclusion that the pandemic is unequal in four ways:

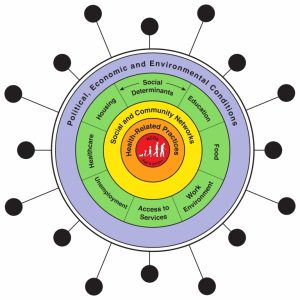

The pandemic kills unequally: COVID-19 deaths are twice as high in the most deprived neighbourhoods of England than in the most affluent, and infection rates are higher in the more deprived regions such as the north-east of England and in urban areas. There are also significant inequalities by ethnicity and race, with the mortality of ethnic minorities in the UK considerably higher than expected, and the death rates of black Americans in US cities such as Chicago far higher than for their white counterparts. This is because of the interaction of the pandemic with existing social, economic and health inequalities.

The pandemic is experienced unequally: the COVID-19 ‘lockdowns’ have resulted in a significant increase in social isolation and confinement within the home and immediate neighbourhood for an average of 10–12 weeks. The social and economic experiences of this lockdown are unequal, as lower-income workers are more likely to experience job and income loss, live in higher-risk urban and overcrowded environments, and have higher exposure to the virus by occupying key worker roles.

The pandemic impoverishes unequally: COVID-19 and the lockdowns have resulted in an unprecedented shock to the economy with widespread predictions of the worst recession for 300 years. This economic devastation will result in job losses, wage reductions, higher debt and more poverty, as well as increases in the ‘deaths of despair’. However, the social and geographical distribution of these economic impacts will be unequal – with low-income workers, women and ethnic minorities bearing the brunt.

These pandemic inequalities are political: the unequal impacts of COVID-19 were not inevitable – the pandemic was a predictable event and its unequal effects could have been mitigated or avoided through better preparation. The original inequalities leading to these unequal impacts were a result of prior political choices, and policy makers could have chosen to address the unequal impacts of the pandemic or not. Governments responded differently and those countries with higher rates of social inequality and less generous social security systems had a more unequal pandemic.

So, COVID-19 is a syndemic of infectious disease and inequalities. It has killed unequally, been experienced unequally and will impoverish unequally. These health inequalities, before, during and after the pandemic are a political choice – with governments effectively choosing who gets to live and who gets to die. Our book concludes by showing how we can learn from COVID-19 quickly to prevent inequality growing and to reduce health inequalities in the future.

Clare Bambra is Professor of Public Health, Population Health Sciences Institute at Newcastle University.

Katherine Smith is Professor of Public Health Policy at University of Strathclyde.

Julia Lynch is Professor of Political Science at University of Pennsylvania.

This post was originally written for the blog Transforming Society and has been re-posted here with their kind permission.