Bristol Poverty Institute COVID-19 Webinars

Poverty Dimensions of the Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 on Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) Communities

Thursday 30 July, 14:00-16:00 (online)

On Thursday 30 July the Bristol Poverty Institute (BPI) held the second webinar in our ‘Poverty Dimensions of COVID-19’ series: Poverty Dimensions of the Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 on Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) Communities.

The webinar had over 60 attendees representing a range of sectors and organisations including civil sector, local and national government, national and international NGOs, consultants, and academics from around the world. This diverse audience was deliberate: the series has been designed to bring together a variety of participants representing different sectors, with a range of theoretical, methodological, and disciplinary approaches. We recognise that different professional, academic, and civic communities will have access to different sources of information, datasets, and tools for analysis, and may also have different immediate priorities. We are, however, all driven by the ultimate aim of reducing the negative impacts of this global pandemic on all aspects of society, and particularly on those communities and individuals who are already experiencing disadvantages. By bringing together a range of perspectives we sought to improve our understanding of the poverty dimensions of this pandemic, and by extension our ability to influence policy and practice in order to mitigate its negative impacts.

Our webinar on the ethnic inequalities associated with COVID-19 featured four fantastic speakers who explored different dimensions from different perspectives. Each talk lasted 15minutes, with opportunity for a short Q&A following each presentation. The slides from these presentations will be available shortly on the BPI website, and in due course we will also be uploading recordings of the presentations.

Before launching into the presentations I (Lauren Winch, BPI Manager) alerted the audience to the fact that UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) have launched a highlight notice on their COVID research funding call, with a specific focus on understanding the reasons for vulnerability to COVID-19 and differentials social, cultural, and economic impacts of the pandemic on minority ethnic groups.

Dr Saffron Karlsen, Understanding ethnic inequalities in COVID-19

The first speaker was Dr Saffron Karlsen, Senior Lecturer at the School for Sociology, Politics, and International Studies at the University of Bristol.

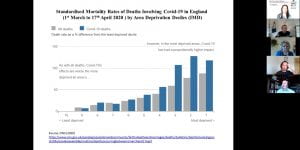

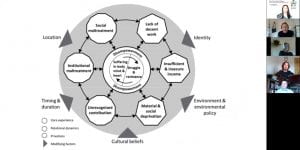

Saffron’s presentation gave an overview of the evidence of the presence and explanations for ethnic inequalities in COVID-19 in the UK, rather than focusing solely on the poverty aspect. She began by highlighting how the first deaths in the UK were BAME doctors and nurses and data showed that BAME groups were more at risk of contracting and ultimately dying from COVID-19. The results were unsurprising for those looking at health and ethnic inequalities, as they are similar to patterns for other health conditions. Her presentation highlighted the various dimensions of inequality which contributed to the increased risk and impact of COVID-19 in these communities. For example, individuals from BAME backgrounds are more likely to be in key worker roles and therefore more at risk of contracting the virus, as well as relying heavily on public transport.

Ethnic variations and occupational position and employment status have persisted since the 1970’s, and for some groups are getting worse. Saffron noted how these structural inequalities are not only important because of the impact of COVID-19 but have also led to other problems which disproportionately affect ethnic minority communities in lockdown. For example, overcrowding in BAME households has been found to be a factor for impact and is often presented as cultural preference rather than a financial problem. Poverty has a huge impact on food choices and obesity, which links to susceptibility and severity of infections such as COVID-19. Saffron closed by emphasising that those with privilege must use it to hold people to account, to make change happen and to elevate unheard voices.

At the end of the webinar Saffron also encouraged participants to engage with a survey being run by the University of Bristol and Black South West Network to find out more about the pandemic experiences of BAME people in the South West. The survey can be accessed via this link. For more information please contact Rosie Nelson rosie.nelson@bristol.ac.uk.

Saffron’s presentation is available here.

Dr Andrea Barry, The coronavirus storm: exposing pre-existing racial inequalities and poverty in the UK

The second speaker was Dr Andrea Barry, a Senior Analyst at Joseph Rowntree Foundation leading analysis for their work outcome group. Andrea began by talking about pre-existing racial inequalities and factors which mean that certain people will be affected by COVID-19 more than others. Andrea’s approach looked at the pre-COVID-19 picture around poverty, housing, income, and ethnic inequalities, and how this has been impacted by the Coronavirus ‘storm’.

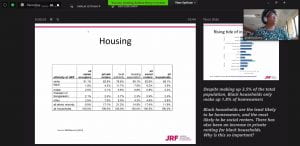

To illustrate this Andrea provided statistics on home ownership vs. rental and how this intersects with poverty, the rise of in-work poverty over the last twenty years, and how different groups have been disproportionally affected by poverty.

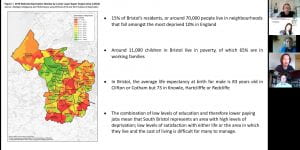

She also explored how both rates of poverty and proportions of the population classified as ethnic minorities were higher in certain areas and the potential correlations between these, highlighting London and the West Midlands as particular examples.

Andrea went on to explore the multiple factors that influence it citing the fact that being in low paid work makes it difficult to escape poverty, and that if you are a BAME household you are disproportionately more likely to be private renting and more likely to be in social housing accommodation. In addition, the pre-COVID picture for BAME communities in poverty looks very different which is partly down to peoples work and work status, for example whether they work full time, part time or are self-employed. Those working in food, accommodation and retail sectors were at greatest risk of in work poverty. Andrea also explored a range of other factors including pay inequalities, wealth gap comparisons, poverty-linked health issues, and debt, all of which are disproportionally impacting on BAME communities and exacerbated by COVID-19.

Andrea concluded with some recommendations which would help tackle some of these issues:

- An increase to the local housing allowance to cover median rents in areas and access to affordable housing.

- Relaxing labour market constraints and removing barriers and inequities to alleviate in work poverty.

- Strengthen the support for self-employed people in Universal Credit by removing the minimum income floor rule.

Andrea’s presentation is available here.

Ms Chiara Lodi, Economic impact of COVID-19 on black, Asian and minority ethnic businesses and communities

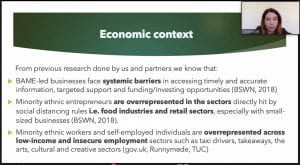

The next speaker was Chiara Lodi, a Policy and Research Officer at Black South West Network (BSWN) and the lead author on their recent report on the Impact of COVID-19 on BAME Led Businesses, Organisations and Communities.

Chiara opened by introducing the fact that BAME communities are mathematically over exposed to COVID-19 due to being overrepresented in food industries and the retail sector, as well as being overrepresented in low income and insecure employment such as taxi driving and takeaways, echoing points made by Andrea previously. Financial insecurity, low quality housing and mental health all interconnects making this a socio-economic picture and not just about economics. She highlighted how structural inequalities are not only placing BAME groups at much higher risk of severe illness from COVID-19 but also creating conditions for them to experience harsher economic impact from the government measures to slow the spread of the virus.

Chiara explained that BSWN knew from the beginning that there would be a disproportionate impact on BAME, and their response was therefore immediate. They issued a survey straight after lockdown to access the impact on BAME led businesses, social enterprises, voluntary organisations, and self-employed ethnic individuals. National financial support packages were available from the start, but BSWN wanted to identify systematic barriers that communities had with trying to access support. The research found that sectors where BAME people were overrepresented, those working low income jobs, the self-employed, and the charity events and voluntary sector are the hardest hit by the economic environment of COVID-19 and the government’s response to it. At the same time structural barriers hinder the sectors access to the national financial support packages. Self-employed people were the most worrying sector for analysis as there was no support for low income self-employed workers or people on zero-hour contracts who were unable to work.

Chiara concluded by highlighting that BSWN continues to monitor the impact and collect key evidence for a recovery strategy for the sector. They are also working with Saffron Karlsen and others at the University of Bristol to identify the impact of COVID-19 on health. BSNW are continuing their work with business and voluntary community networks with webinar sessions and have also launched the ‘Back Her’ business programme which focuses on black female entrepreneurs. More information is available on their website.

Chiara’s presentation is available here.

Dr Soumya Chattopadhyay, COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on the global poor: Pathways, patterns and concerns

The final speaker was Dr Soumya Chattopadhyay, a Senior Research Fellow in the Equity and Social Policy Programme at Overseas Development Institute (ODI) who was previously in the Poverty and Equity Global Practice at the World Bank.

Soumya’s focus and analysis was more about the impact of COVID-19 from a global perspective. He explained that direct linkages to BAME might not translate directly; however, every country has its own group of vulnerable and marginalised communities and these would be his focus. He began by explaining how COVID-19 infection, recovery and health economics vary by country. He also noted that the more affluent countries are more mobile, so the pandemic transferred quickly across borders whereas other countries may not yet have hit their peak of the virus. Soumya noted that COVID-19 has been called a ‘disease of poverty’ and there is a vicious cycle between poverty and health vulnerability. He reported that World Bank predicts 70-100 million people will enter extreme poverty in 2020, which is classified as living on less than $1.90USD per day.

Echoing comments made in previous presentations Soumya explained how poor people are more exposed to the pandemic due to factors including the nature of their work and their health conditions. For example, only 26% of people living in rural Bangladesh have access to running water with soap, and most developing countries do not have access to reliable and affordable healthcare systems. Soumya did note, however, that some developed countries also suffer from this problem as health insurance is often linked to jobs meaning that if you lose work; you lose health cover.

Soumya explained that the economic channels for increased vulnerability are loss of employment from sickness or caregiving, loss of earnings and employment in lockdown, Inability to work from home, low wages, and the lack of a social protection system. Anyone working informally or seasonally does not exist in a universal database so in many cases are ineligible for any financial support from government. He also reported that as countries ease restrictions there has been some re-emergence’s of COVID-19. Lockdowns in some cases (particularly India) led to people trying to migrate and people lost lives trying to get back to their native place. Soumya questioned how governments, policy makers and individuals could respond to the risk involved, noting that most governments have utilised any surplus and borrowed heavily to meet the crisis so their ability to keep giving social protection is hampered. Soumya concluded by emphasising that data driven policy interventions and disaggregated data is needed now more than ever.

Soumya’s presentation is available here.

Slides from all presentations are available on the BPI website, and we hope to upload recordings of the presentations shortly.