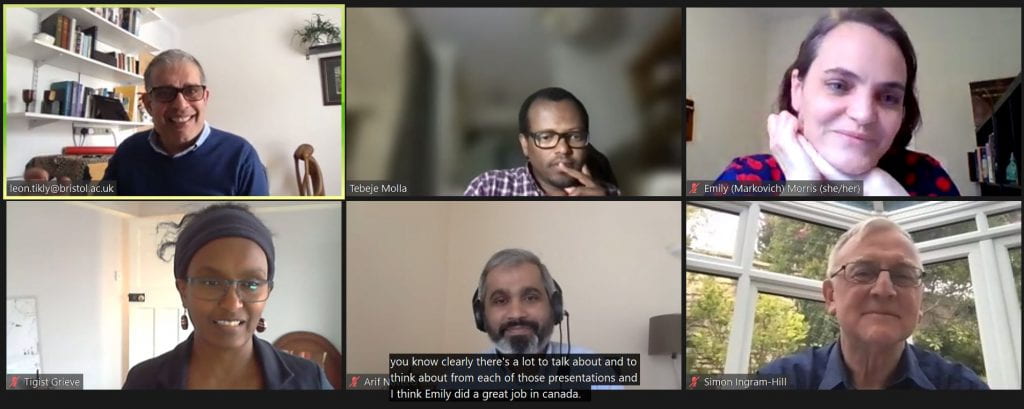

This blog post was coordinated by Dr Tebeje Molla (Deakin University, Australia) and Dr Tigist Grieve (University of Bristol, UK), with contributions from Prof Leon Tikly (University of Bristol, UK), Dr Emily (Markovich) Morris (American University, Washington D.C., USA), Dr Arif Naveed (University of Bath, UK), and Mr Simon Ingram-Hill (former Country Director for the British Council in Sierra Leone, Mozambique, Hungary, Mauritius). All views expressed are those of the contributor(s) cited.

Introduction

As part of the Bristol Poverty Institute Conference, Poverty and the Sustainable Development Goals: From the Local to the Global (27-29 April 2021), an international group of scholars held a round-table discussion on education and poverty. The session was convened by Prof Leon Tikly and Dr Tigist Grieve. The panellists shared empirical findings and analytical reflections on the topic. However, we had limited time to answer questions posed by the chair Prof Leon Tikly at the end of the session. This short blog post therefore collates our responses to the questions. The video recording of the session along with some of our presenters’ slides can be found on the Bristol Poverty Institute website.

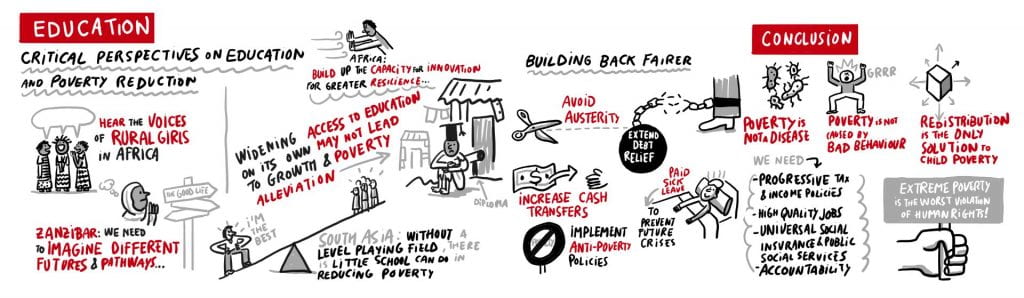

Visual Minutes of the Session (Credit: Bristol Poverty Institute, Jorge Martin Illustrator)

Discussion

Question 1: Tigist, how do we ensure the voices of rural girls are heard by policy makers?

Tigist: In answering this question, I am highlighting a piece of writing from my doctoral research. It has sections on voices and while it is a bit of a long response it captures my take on the issues of voice overall. In practice, it is notoriously difficult to get a hearing from policy makers even to the recommendations from senior scholars and established institutes let alone from girls. The possibility of getting voices of people living in rural areas heard and then taken seriously in the policy sphere is unattainable. In sum, I would say in the majority of cases where claims are made about ‘voices of the poor’ it is a proxy one. For further discussion and critical perspectives on this see (Chambers, 1997; Holland and Blackburn 1998; Boyden and Ennew 1997; Hart 2013; Morrow 2001) for example.

To begin with, there is limited direct link between the people in the policy sphere and academics engaged in research. Where there is direct link, there is a filtration of voices even within the academic sphere where those researchers on the ground perhaps with direct access to those voices are not the same as those who make the final call in the analysis, in how data is interpreted, what gets stripped away and what gets amplified. Further, the voices are diluted to fit academic style outputs, or policy briefs and so on. Some established academics may get a hearing as government advisors and I am sure they do their best in maximising the opportunity to influence policy but that is a rare privilege and available for few. I don’t want us to misunderstand that I am arguing or expecting the voice to become policy rather I am saying a policy anchored on lived experience of people, responding to their concerns and that takes into account the impact of decisions e.g. the complex interplay between education, poverty and gender as we are speaking now will be impacted by decision for withdrawal of services, change in procedures and so on. For more about policy making please refer to the following publications:

- Globalizing Education Policy (Fazal Rizvi and Bob Lingard);

- Education Policy and Social Class (Stephen J. Ball).

Further, although community consultation can ideally be instrumental in ensuring that the voices of girls are heard, structural issues including repressive gender culture means that it might be difficult to hold open and free discussion in rural communities (see Tebeje’s comments below). Even when you are entrusted by communities and successfully consult, as anthropologists and ethnographers do, you may generate so much knowledge (data), but you know deep down the complexities of utilising that into policy that can genuinely transform their situations.

Moreover, I am aware despite the increasing popularity of voice in social research and development discourse there are many questions over its practical application and at times it remains a rhetorical device (Wells 2009:182; also see Komulainen 2007). Commitment to voice should not blind us to the importance also of going beyond the immediate social worlds of children to theorise how children’s everyday lives are shaped and reshaped through globalization as well as political and economic conditions (see relevant discussions for this in Abebe 2020, Boyden 1997, Hart 2008, Katz 2004, Komulainen 2007; and for education-related policy relevant discussions see Crossley 2001, Tikly & Barrett 2013).

Generally, there is limited evidence of where girls’ voices from rural context influence policy. Having said that, we must also acknowledge the mighty but small-scale work by genuinely engaged third sector organisations, communities themselves and activists. In this context it is possible to hear and act on the voices of girls in small ways but still transformative in changing practices on the ground. To sum up, as we seek to amplify voices or for this to be part of transformative agenda in relation to gender equity in education, I want to draw our attention to recent critical contributions on the topic and call for greater sensitivity to the way voices of (children, teachers, communities) are interpreted in scholarly and policy circles.

Question 2: Emily, how might the Zanzibarian government most effectively respond to drop out? Ought they to focus on in school or out of school factors primarily (e.g. labour markets)?

Emily: Governments (Zanzibar and beyond) can start using the term pushout, recognizing that the majority of young people do not leave on their own volition and start tracking why young people are leaving, as well as listening to youth narratives of push-out and pull-out (echoing Tigist’s research).

In the case of Zanzibar, school quality – when linked with geography and familial poverty – is a major contributor to youth being pushed out of school and therefore an integrated approach to improving school quality is needed (for example better teacher training, increased guidance and counselling, accessible tuition/tutoring in difficult subjects like English) to ensure youth are not pushed out as a consequence of failing the exams (I echo all of Arif’s points on quality, see below).

Also, governments need to recognise that the human capital theory has its limitations when there is a small formal economy and large inequities in income based on geography, gender, and other factors (linking to Arif’s work on rate of returns and his points above). While Zanzibari boys tend to associate education with economic ends, this is not always the case for girls who see intrinsic and extrinsic value to education beyond economic ends. Thus collaboration between Ministries of Labour, Social Welfare, Women, and Children are critical to ensuring that education is relevant to the aspirations of youth of all genders and geographies (linking to Tigist and Tebeje’s points). Looking at the curricula and how school is preparing youth for different futures is part of ensuring education is relevant, as well as ensuring that youth have the support needed to navigate the many barriers and obstacles they encounter while trying to achieve “the good life.”

Question 3: Tebeje, how might the Ethiopian government go about evaluating and prioritising the capability set for learners in Ethiopia?

Tebeje: Educational capability refers to people’s genuine options to be well educated. It is widely seen as a foundational capability that expands human freedom in other spheres of life.

Achieved educational outcomes are observable and easy to assess. Whereas educational capability sets may not be readily discernible, we can only access those through indirect means of assessment. To begin with, governments can evaluate and prioritise the capability sets of learners through two interrelated processes. First, to understand the substantiveness of opportunities of equity targets, one can start with assessing observable outcomes of the group. It is a backward process that proceeds from the outputs to inputs. The focus is on what genuine options people have to achieve alternative functionings. For instance, policymakers who are interested in addressing gender inequality in education may visit rural schools. A high level of gender inequality in those schools may force the visitors to ask about real options that girls in the area have to participate in education and training.

But such evaluative processes cannot provide a complete picture about substantiveness of educational opportunities and conversion abilities of individuals. For example, a backward evaluation does not tell us why two groups or individuals with similar educational capability sets might end up achieving different levels of outcomes. A young girl from illiterate farming families in rural Ethiopia and a boy from high-paid professional parents in Addis may have equal access to basic education (in terms of having a publicly funded school nearby) but they are surely not equally positioned to take advantage of the opportunity. Conversion abilities of the two students vastly vary. Hence, there is a need for a complementary process, namely public consultation. Broad-based community consultation enables governments to understand specific conditions and needs of equity target groups such as girls in rural areas, students with disability, and learners from historically marginalised ethnic groups. Clarity on those issues, in turn, makes it possible for policymakers to ensure that educational opportunities are adequate, relevant, and convertible.

Still, public consultation is not without limitations. The notion of public reasoning presupposes a democratic political culture where people freely and reflectively express their wishes. In reality, as Sen notes, “the way people read the world in which they live” can be obscured by relational and structural factors around them. Hence, due in part to political, cultural, and social barriers, people in less democratic countries (e.g. Ethiopia) may not be completely free to articulate their needs and aspirations during public consultations.

Question 4: Arif, what are the two or three top priorities for South Asian governments who wish to use education to combat poverty?

Arif: I feel there are a few things that the governments could do to enhance the transformative potential of schooling in the lives of the poor in South Asia.

First, the quality of education needs to be improved drastically, specially at the basic levels. The kind of schools and schooling that have been made available to the poor do not enhance their skills that are economically rewarding or even help them pursue further schooling. The unprecedented expansion of education in the last 2-3 decades has led to the overcrowded and under-resourced classrooms with children graduating without acquiring literacy and numeracy skills. Without significant improvement in quality, the levels of schooling that poor can realistically acquire cannot help them break out of poverty.

Second, the evidence from the longitudinal studies points towards a targeted approach for the poor families as universal approaches do not serve them. Poor children are more likely to drop out of schools at early stages. Scaffolding their academic progression and helping their transitions into decent work are essential. Third, economic opportunities are fundamental for the poor families’ educational decision-making. If the labour market doesn’t provide a fair chance to everyone, and poor are less likely to gain decent employment through schooling, the goals of universalising educational access and eradicating poverty through it cannot be realised. Transforming labour markets however requires a wider set of reforms that address all forms of social inequality at the community levels, and the national and global power structures that determine the possibilities of economic growth in the regional countries.

Question 5: Simon, based on your rich experience, which country that you have worked in has been most successful in tackling poverty and what role did education play?

Simon: This is a difficult question to answer as my direct experience in each of the six Sub-Saharan African countries I worked in from the mid-80’s (Cameroon, Sudan, Ethiopia, Mozambique Mauritius, and Sierra Leone) was time-bound and came at different historical points in the struggle to alleviate poverty. Each, except notably Mauritius, was facing very significant internal challenges such as Ebola in Sierra Leone in 2014/15, or were recovering, five to ten years on, from hugely destabilising civil conflicts as in Mozambique, Ethiopia and Sierra Leone. But global factors have also been critical. For example, Sierra Leone’s economy was already suffering from the 2013 collapse in global iron ore prices which made its recovery from Ebola all the more difficult.

Statistics tell different stories, some suggesting a degree of stagnation in the standard of living in certain countries over the last 30 years; however, World Bank GDP per capita figures do show a steady improvement in all six countries with significant dips where crises have occurred. Covid-19 is set to continue this pattern.

Within education, increases in access and latterly of quality have taken place. While these cannot be stated as directly causing poverty reduction, some initiatives such as increasing girls’ education can be seen to have an impact on social development. For example, evidence suggests each additional year of a girl’s secondary schooling can reduce the chance of pregnancy by approximately 6%.

The richer the country, the better it has fared. Mauritius has been able to tackle its own economic challenges more successfully – as on the removal of the EU sugar subsidy, through greater diversification of its economy. At the other end of the scale Sierra Leone has taken some important education decisions with its 2015 National Ebola Recovery Strategy. It has focused on improving teaching quality and skills-based learning at primary and secondary levels and increasing the relevance of higher education curricula to create a more effective workforce. These strongly suggest how that country sees the interconnections between education and poverty alleviation.

Round-table Discussion Participants

Prof Leon Tikly (Global Chair in Education and Director of the Centre for Comparative and International Research in Education, School of Education, University of Bristol, UK).

Dr Tigist Grieve (Senior Research Associate, School of Policy Studies, University of Bristol, UK)

Dr Emily (Markovich) Morris (Director of International Training and Education Program and Senior Professorial Lecturer, School of Education, American University, Washington D.C., USA)

Dr Tebeje Molla (DECRA Fellow, Deakin University, Australia).

Dr Arif Naveed (Lecturer, School of Education, University of Bath, UK).

Mr Simon Ingram-Hill (former Country Director for the British Council in Sierra Leone, Mozambique, Hungary, Mauritius).

Recordings and presentation slides from the full round-table discussion are available on the Bristol Poverty Institute’s conference webpages.