The Bristol Poverty Institute (BPI) is now closed and will no longer be producing blog posts.

Category: Uncategorized

BPI Seedcorn Fund Projects 2024-25 Showcase – 26 June 2025

Another year and another round of BPI Seedcorn funded projects are nearly complete! This year’s showcase (held on the 26 June 2025) began with a look at what the BPI do and how the BPI supports poverty research by offering a Seedcorn fund, before moving onto the presentations explaining each of the three projects funded in this round (i.e. in the 2024-25 academic year).

Joe Jezewski, the BPI Development Associate, explained in the introduction that the BPI’s overarching goal has not changed – to achieve SDG 1: ‘to end poverty in all its forms everywhere’ – and that the Seedcorn Fund, which offers new research projects small sums of £3000-£6000, is one of the key BPI initiatives that sustains the BPI’s trajectory towards this goal. The money can be seen as ‘kick-starter’, to get great poverty-research projects off the ground and lead towards larger funding bids once the projects are established.

Following Joe’s presentation, we then moved into the project showcase section of the afternoon with Dr. William Baker presenting first on his project entitled ‘Low wage work in the education system: food banks and food insecurity’. Will began by explaining the background and impetus for his project which highlighted that 3+ million children live in food insecure households in the UK and that 20% of schools in England now have a food bank – which is over 4000 schools (which means there are now more foodbanks inside of schools than outside. And for context, in 2010 Trussell Trussell operated 35 food bank centres, but by 2019/20 this had risen dramatically to 1,400. Source). Emerging evidence suggests that school staff on low incomes – from teaching assistants, catering workers, administrative staff, and parenting school staff – are also using school-based food banks.

As such, Will’s project, which is being co-produced with the trade union, UNISON, (and co-investigator Dr Sarah McLaughlin) aimed to examine the experiences of school staff who have reported using school-based food banks. Although data collection is ongoing and the research not complete yet, early indications from the empirical study involving interviewing 20 school staff members show that there are key themes that create food insecurity. Themes Will highlighted were – Covid-19 and the cost-of-living-crisis, low pay, teaching assistants who are typically not paid very well being seen as a flexible part of the workforce, insecure term-time only work (with insecure roles being the last to be recruited and the first to be let go), and challenges with Universal Credit and the 2 child benefit cap. In the discussion that followed Will’s presentation, it was also mentioned that there is no government funded element for food bank work in schools and that school breakfast clubs are only given 75% of the budget they need for this – which puts further strain on school finances.

Dr. Alisha Suhag went next and presented on her project entitled ‘Ultra-Processed Foods (UPFs) and Health Inequalities: A data-driven approach to understanding socioeconomic disparities in diet’ (project co-investigators: Professor Jeff Brunstrom and Dr Anya Skatova). Alisha began by explaining their plan to collect information on UPF consumption by using Tesco loyalty card data which would give them access to vast amounts of real-world behaviour information; the motivation for the project being to analyse the rising consumption rates of UPFs in the UK, especially within lower-income populations. UPFs are industrially formulated products designed for profitability, convenience, and hyper-palatability, accounting for over 50% of energy intake in the UK. UPF consumption is linked to adverse health outcomes including increased risks of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, and a 31% higher mortality rate among the highest consumers – and the project aims to explore these relationships.

Alisha went on to explain that through this scalable, data-driven approach using supermarket loyalty card data, the project will generate insights into the socioeconomic factors driving poor dietary choices and health. The sample size they are working with is 700 UK residents who have been using a Tesco Clubcard for a minimum of 1 year, and the project is just arriving at the survey roll-out and data collection phase now having been through ethics approval. In the discussion there was talk of how one of the key elements of this study is UPF food classification. The team plan to pay particular attention to this to ensure classification is accurate and suitable, and to provide a good basis for running regression analysis which will test associations between UPF spend and health outcomes (e.g. BMI, digestive symptoms and EQ-5D).

The third and final presentation came from Dr Marii Paskov who presented together with Co-Investigator Mrs Katie Cross on their project entitled ‘Poverty and financial wellbeing in the UK: an intersectional approach’ (the project’s 2nd co-investigator is Mr Jamie Evans). They began by explaining that their study focus was to answer this question – ‘Does financial wellbeing vary among individuals living in poverty and if so, why?’. From here they dived into an explanation of what financial wellbeing means and indicated that it can include objective factors, like the individual’s ability to meet needs or pay an unexpected bill, and subjective factors which refer to a feeling of security or its opposite – the experience of financial stress. They also explained that their aim was to establish how specific dimensions of inequality – gender, age, and ethnic-racial background, and health – intersect with poverty to shape experiences of financial wellbeing.

Marii and Katie then presented some initial results having analysed data from the Money and Pensions Service’s Financial Wellbeing Survey. These showed different patterns among different groups, for example, that females experienced less financial satisfaction than males. Disabled people also experienced less financial satisfaction than those non-disabled. Generally, their analysis of households in income poverty showed that such households could experience varying levels of financial wellbeing because of 3 dimension: intersectional inequalities (e.g. having multiple vulnerabilities such as being disabled and a single parent), access to (or lack of access to) support systems (e.g. advice services or family support) and financial literacy (skills to manage finances). In the discussions that followed, Marii explained that further analysis would be needed to understand more deeply why for example, 40% of people on low incomes could meet a bill but 60% couldn’t; and how multidimensional aspects of poverty are significant to a holistic understanding of why some groups obtain help and others don’t. The conversation also covered aspects such as the inadequacy of Universal Credit (UC) to support those in poverty, not just in terms of the amount of money received but also the conditionality aspects to obtaining UC.

Overall, it was a great afternoon of learning and discussion and we wish our three teams all the best in finalising their projects and disseminating their findings – we look forward to reading those reports and journal articles! The slides from the project presentations are also available via our event resources page.

Poverty and Benefit Cuts

Author: David Gordon, Director of the Bristol Poverty Institute

The Labour Government was elected in 2024 on a manifesto which promised to; ’develop an ambitious strategy to reduce child poverty’ and ’slash fuel poverty’ and ‘create a world free from poverty on a livable planet’. After the election, Kier Starmer argued that ‘no child should be left hungry, cold or have their future held back’ and Liz Kendall (DWP Minister) said ‘We will turn the tide on rising poverty levels, so that every child no matter where they come from has the best start in life.’

However, the details released in March about the cuts/changes to disability and health benefits show that poverty and inequality will rise over the next four years to help fund increases in military expenditure. The cuts are estimated to reduce the social security budget by £4.5 billion by 2029/30 and 3.2 million families incomes will fall, with an average loss of £1,720 per year.

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) Impact Assessment estimates that the changes will result in an additional 250,000 people (including 50,000 children) in low income poverty (After Housing Costs) by 2029/30.

The DWP’s poverty baseline model assumes that the previously announced changes in both the Labour and Conservative government’s budgets will be implemented and predicts that child poverty will increase by more than half a million by the end of the decade. The model thus includes the proposed Conservative Government’s changes to the Work Capacity Assessment (WCA) which were found to be unlawful by the High Court in January 2025. The WCA changes would have reduced the benefits of over 400,000 disabled people and resulted in an additional 150,000 working aged adults and 50,000 children living in poverty by 2029/30.

Including the proposed Tory WCA changes, which were never going to be implemented by Labour, in the baseline DWP poverty model obscures the scale of the health and disability benefit cuts and their poverty impacts.

The New Economics Foundation (NEA) estimates that the ‘true’ amount of the health and disability benefit cuts is £6.7 billion and this will increase poverty by 340,000 people by 2029/30.

Even before these benefit cuts, the number of poor children (4.5 million) was higher than at any time during the past 30 years.

Almost all the families that lose financially have someone with a disability in their household. Joseph Rowntree Foundation funded research has shown that even before these latest benefit cuts, half of the people receiving the health-related element of Universal Credit (LCWRA) are either unable to heat their home, behind on bills, or have low or very low food security. Similarly, a quarter of working-age adults in a family receiving health-related UC have had to use a foodbank in the last year.

The benefit cuts and budget changes will also result in greater inequality, with the poorest 33% of people seeing their incomes fall by 8%, while the richest 33% do not lose any income on average (see Figure below)

The incomes of poor households (After Housing Costs) will also fall i.e. the poor will become poorer.

The Labour Government is actively working on a child poverty strategy as they promised (I am one of many academic advisors they have consulted). However, poverty was mentioned only once in Rachel Reeves budget speech in October and the health and disability cuts in the Spring Statement will both increase child poverty and reduce the incomes of tens of thousands of children in households where someone is disabled. There will be more poor children and some of the poorest children will become even poorer.

Pathways to Work: Reforming Benefits and Support to Get Britain Working Green Paper

Author: David Gordon, Director of the Bristol Poverty Institute

The DWP published a Green Paper on the 18th March outlining its proposed changes to the health and disability benefits system and for employment support. The government has launched a consultation to seek views about their proposed changes which will close on 30th June 2025.

The proposed changes included some positive elements, such as a £7 per week increases to Universal Credit, an additional £172 million for the Disabled Facilities Grant over the next 2 years, an additional £1 billion employment, health and skills support package and scrapping the Work Capability Assessment (WCA) by 2028.

Unfortunately, the Green Paper also proposes that largest cuts to disability benefits in UK history (£5 billion by 2030).

The £5 billion ‘savings’ will be made by increasing the disability severity eligibility thresholds required to claim Personal Independence Payment (PIP) and reducing the amount of additional disability-related support for new Universal Credit claimants by almost half (from £97 to £50 per week), freezing the £97 for existing claimants and possibly removing eligibility entirely for young people aged 18-22. The Resolution Foundation has estimated that about 1 million people may lose their PIP benefit entitlement. The reduction in the limited capability for work and work-related activity (LCWRA) in Universal Credit will reduce the incomes of many of the most severely disabled adults.

Eligibility for LCWRA includes;

- People who have a life expectancy of less than 12 months, or

- Those waiting for, receiving or recovering from chemotherapy or radiotherapy, or

- Pregnant women where there is a serious risk of damage to their health or the health of the baby if they do not stop work-related activity.

- People whose disability is scored 15 points on any indicator of Activities of Daily Living (ADL).

Examples, of the severe levels of disability required to claim LCWRA include;

- Cannot convey a simple message, such as the presence of a hazard – 15 Points

- Cannot raise either arm as if to put something in the top pocket of a coat or jacket – 15 Points

- At least once a week, has an involuntary episode of lost or altered consciousness that causes significant reduction in awareness or concentration – 15 Points

- Reduced awareness of everyday hazards so that there is a significant risk that they will hurt themselves or others, or damage property or possessions, so that they need supervision most of the time to stay safe – 15 Points

The morality of removing and reducing benefits claimed by severely disabled adults is questionable, particularly given the high and increasing rates of poverty that affect many disabled people and their families.

The most recently available UK poverty statistics, for 2022/23, show that there were 6.2 million people living in low-income poverty (after allowing for housing costs) in families that included a disabled adult or child. Which was 43% of all poor people.

However, the official poverty estimates have been shown to significantly underestimate the poverty of disabled people as they do not make adequate allowances for the known additional costs of disability. The Social Metrics Commission has recalculated the official poverty measure using more realistic estimates for disability costs and found that;

“More than half (8.7 million; 54%) of all people in poverty live in a family that includes a disabled person. Three in ten (31%) of those in poverty are themselves disabled: a total of 4.9 million people.” Measuring Poverty 2024, p9

Source: https://socialmetricscommission.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/SMC-2024-Report-Web-Hi-Res.pdf

The poverty data for 2023/24 will be released on the 27th March 2025 and may show that poverty amongst disabled people has continued to increase.

It should be noted that the Social Metrics Commission is run by the Centre for Social Policy – a Conservative Party think tank. Academic estimates of poverty amongst disabled people in the UK could be higher than those produced by the Social Metrics Commission.

To conclude, the Green Paper proposals outline a grim future of increasing poverty and destitution for many disabled people, particularly some severely disabled young people. Low income poverty rates, hunger and food insecurity are already high and increasing amongst disabled people and their families. The proposed £5 billion in benefits cuts will inevitably make this situation worse.

Source: https://www.jrf.org.uk/deep-poverty-and-destitution/from-disability-to-destitution

Abandoning the Poor – US and UK Aid Budget Cuts

Author: Professor David Gordon (Director of the Bristol Poverty Institute)

At midnight on Sunday 23rd February 2025, USAID (the world’s largest provider of international aid – circa $69 billion) was effectively shut down by the US Government on the direct orders of President Trump. Almost all direct hire staff were placed on administrative leave and notice was given that 1,600 permanent staff would be sacked. A six-week purge of USAID’s work, which ended on 10th March, resulted in 5,200 development programmes being eliminated out of a total of 6,200.

On the 25th February 2025, Kier Starmer announced that the UKAID budget (circa $19 billion) would be reduced in 2027 from 0.5% to 0.3% of Gross National Income (GNI) to fund an increase in Defence spending. On 28th February, Anneliese Dodds (International Development Minister) resigned arguing that these cuts would “remove food and healthcare from desperate people – deeply harming the UK’s reputation”.

The likely effects of these cuts are becoming clearer. On 4th March, Nicholas Enrich, (USAID Acting Assistant Administrator for Global Health) wrote a 20 page memo on the ‘Risks to U.S. National Security and Public Health: Consequences of Pausing Global Health Funding for Lifesaving Humanitarian Assistance.’ He estimated that every year there would be an additional:

- 2-3 million child deaths due to a lack of immunisation against vaccine preventable diseases

- 1 million children per year will not receive treatment for severe Malnutrition

- 8 million pregnant women would not receive maternal health care

- 7 million children will not receive medical treatment for Pneumonia and Diarrhoea (the largest cause of death for children under 5)

- 3 million babies will not receive postnatal care in the two days after birth

- 71,000-166,000 deaths from Malaria and 12.5-17.9 million more cases

- 200,000 paralytic Polio cases

- 127,000 Monkeypox virus cases

- A 28-32% global increase in TB and Multi Drug Resistant TB cases

- Potentially, 28,000 more cases of Emerging Infectious Diseases, such as Ebola, Marburg, etc.

The huge cuts to USAID will inevitably result in the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal targets not being met. On 4th March, the US told the United Nations General Assembly that;

“President Trump also set a clear and overdue course correction on gender and climate ideology, which pervade the SDGs….Put simply, globalist endeavours like Agenda 2030 and the SDGs lost at the ballot box. Therefore, the United States rejects and denounces the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals,‘

We do not yet have robust estimates of the likely effects of the proposed cuts to UKAID. However, the Independent Commission for Aid Impact produced a report on the 26th February, detailing how UK aid is currently spent. The most concerning findings were that:

- The UK development budget has seen dramatic reductions since 2020

- A substantial share of UK development funding is currently spent within the UK (see Figures 13 & 14 below)

- Allocations to longstanding UK country partners have been significantly reduced

- The UK’s ability to respond to humanitarian crises has been reduced (see Figure 6 below for context)

- Apart from in-donor refugee costs, other government departments now spend less development funding

- The Sustainable Development Goals are significantly off-track

- International climate finance falls significantly short of developing country needs (see Figure 2 below)

- Rising conflict is placing heavy strain on the international humanitarian system

- Global finance is now flowing away from developing countries

Figures from the ICAI report on UK aid spending

Conclusions

The USA and UK are dramatically reducing their funding on international aid and abandoning the poorest and most vulnerable people. It was of course not always this way and so I will leave you with some quotes from previous US Presidents about the need to reduce poverty and increase human rights.

“The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.”

– Franklin D. Roosevelt (US President 1933-1945)

“Freedom means the supremacy of human rights everywhere. Our support goes to those who struggle to gain those rights and keep them. Our strength is our unity of purpose. To that high concept there can be no end save victory.”

– Franklin D. Roosevelt (US President 1933-1945)

“Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed”

– Dwight Eisenhower (US President 1953 -1961)

“If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich.”

— John F. Kennedy (US President 1961-1963)

My own personal view was nicely summarised by Eglantyne Jebb at the launch of Save the Children at the Royal Albert Hall in May 1919 in front of a hostile crowd many of whom considered her to be a traitor for wanting to help German and Austrian children so soon after the end of the World War;

“Surely it is impossible for us, as normal human beings, to watch children starve to death without making an effort to save them.”

Labour market enforcement, austerity, visas and sustaining poverty

Author: Eda Yazici

Illegalised migrants are often associated with poverty and deregulated labour markets. In this blogpost, I share the experience of one family to show how poverty is created and sustained by, among others, agencies that are supposed to safeguard workers and provide a safety net from destitution. This research was undertaken under the Horizon funded PRIME project that analyses the role of institutions in shaping the conditions and politics of irregularised migrants in Europe.

The context

In 2011, the UK government introduced a deregulatory drive to cut red tape and unleash economic growth (Gov.uk, 2011). This was alongside massive cuts to public spending, decimating local authorities’ ability to support those most in need and suppressing enforcement agencies like the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority’s capacity to investigate labour market abuses. At the same time, the commitment of successive governments to backing “UK PLC” and creating a so-called ‘bonfire of red tape’ has made it easier than ever to start a business. This has enabled the widespread phenomenon of ‘phoenixing’ (WoRC, 2024). Phoenixing is when a company dissolves having come under scrutiny but quickly re-establishes itself under a new name to continue its exploitative practices. The slashed red tape that allows phoenixing to proliferate denies workers redress or practical access to justice.

Phoenixing is particularly prevalent among care agencies who offer Certificates of Sponsorship (CoS) for Health and Care Worker (HCW) visas. HCW visas were introduced in 2021. They tie workers to employers, and if a worker wishes to leave, they must find a new visa sponsor within 60 days or risk deportation. The government sets the cost of applying for a HCW visa at £551 per person for five years. Of the 15 care workers we interviewed for the PRIME Project, the average paid to sponsors was £5000, rising to a maximum of £15,000. Many of the people we met arrived in the UK only to find that the agency who sponsored their visa did not exist, or offered them only a few hours’ work a week, or had phoenixed after having their sponsor licence revoked.

Hameed and Ferhat[1]

Hameed, a data analyst, entered the UK in 2022 on a Skilled Worker visa with his wife, Ferhat, and their two children. Initially, life in suburban southwest London seemed promising and secure, but in late 2023, Hameed was made redundant. This led to the curtailment of his visa, and despite his best efforts, he was unable to secure another visa sponsor for a new job.

Faced with the loss of their livelihood and legal status, Ferhat, who was a primary school teacher in Pakistan, applied for a HCW visa which would allow her to work as a carer, with Hameed and their two children permitted to stay as her dependents. In early 2024, Ferhat found a care agency who promised immediate employment to sponsor her in an Essex town. The family left London, taking a room in a hotel before finding a house to rent. After paying £600 to her new employer to “release the rota”, Ferhat began working as a carer 16 hours a day for 6 days a week. When she complained about the gruelling schedule, the employer threatened her with deportation.

Ferhat’s health deteriorated under these exploitative conditions, and the family faced further obstacles. They could not register with a GP without proof of address and had to visit A&E for medical attention. Despite a sick note, Ferhat was only allowed two days off by her employer before being forced to return to work. The doctor who saw Ferhat did not raise concerns about labour exploitation. Ferhat’s health continued to deteriorate and after several more weeks of working over 90 hours a week, she collapsed at work. Her employer’s response was to summarily dismiss her. The agency who dismissed her has since phoenixed.

In the three months Ferhat was working as a carer, Hameed managed to secure rented accommodation for the family, began applying for school places for their children, and started to look for data analyst jobs. When Ferhat was dismissed, their landlord issued them with a Section 21 or “no fault eviction” notice. Without a new visa sponsor, the family were unable to find alternative rented accommodation and had to return to a hotel. With every penny of their savings spent, and the 60 days to find a new sponsor elapsed, the Citizens’ Advice Bureau advised them to ask their local authority for help.

The local authority reluctantly agreed to support the family under Section 17 of the Children’s Act which places a statutory duty on local authorities to safeguard and promote the welfare of children in their area. Section 17 meets children’s basic needs including food, clothing, and housing irrespective of immigration status. The local authority did not agree to house the family until they sold their last remaining asset – their car – for £300 and had spent that on their hotel room. Despite having no legal right to give immigration advice, the family’s social worker advised them to apply for asylum – support for which is funded by central government, not local government. The family was informed there were no secondary school places available in the local authority for their eldest child and despite a statutory duty to admit children of compulsory school age, the social worker and local authority took no action. Instead, Hameed walked the two miles to the nearest secondary school every day to plead for a place for his son. When his son eventually started school, the social worker did not inform them of the local authority’s duty to make a discretionary payment for school uniform or for travel to and from school, forcing Hameed and Ferhat’s son to start school without uniform and walk four miles each day without a proper coat.

At time of writing the family share a room in a hostel provided by the local authority with vouchers to cover food expenses. Hameed has applied for over 200 jobs as a data analyst hoping that one will sponsor him for a new Skilled Worker Visa. Ferhat has been unable to find an alternative sponsor for a Health and Care Worker visa.

The family’s situation shows the devastating confluence of deregulation, austerity, and a hostile visa regime. The bonfire of red tape allowed the unscrupulous agency to rise and rise again. Austerity has made deep cuts to labour market enforcement agencies and the justice system supposed to protect workers and even deeper cuts to local government. This has left them with minimally resourced social care services desperate to cut costs, cut time, and pass the buck to central government. Finally, the hostile environment and No Recourse to Public Funds prevents many from accessing public services, while a tied visa system prevents those who are exploited from speaking out, knowing that they may pay in deportation. While slashed red tape may unleash growth for care agencies, they are part of a wider system that creates, sustains, and entrenches deep poverty. Ferhat and Hameed’s experiences highlight the need for researchers to not view immigration and other areas of social policy such as work and welfare in isolation and emphasise how different areas of policy come together to create, sustain, and entrench poverty.

[1] Names have been changed

References

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/red-tape-challenge

20240627-worc-evidence-submission-low-pay-commission.pdf

Views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of the BPI and the University of Bristol.

BPI Foodbank Volunteering 2024

The University of Bristol supports all its staff to take one day of volunteering leave per year to help make a positive impact in the local community. This November, the Bristol Poverty Institute (BPI) brought together teams of staff from across the University to return to volunteer at a local food bank and Social Justice Hub, helping out a good cause and having a really rewarding, enjoyable day with colleagues in the process.

This year, we brought together a combination of BPI team members, academic researchers, and colleagues from the Research Development teams in the Division of Research, Enterprise and Innovation. In previous years, our foodbank volunteering days have been largely focussed on sorting through donated food items in the warehouse; however, this year was a little different! In a few weeks, the foodbank will be handing out Christmas presents to the customers who rely on the foodbank, bringing a little Christmas joy alongside their usual food parcels. We were therefore tasked with working through dozens of boxes of donated gifts, wrapping them up, and allocating them to the most suitable age and gender category.

We bundled together different value and types of items to make nice gift-worthy combinations. For example, a mix of bath products and some colourful scrunchies, a book and a toy, or a necklace and a pair of socks. It was really fun putting together combinations which we thought people might like, and we really hope that the presents help bring some extra Christmas cheer to people struggling in the face of the cost-of-living crisis. We wrapped A LOT of presents and had a great time doing it, and towards the end of the day we were already having a chat about volunteering at the foodbank again next year!

Before heading home, I had a chat with the foodbank’s Assistant Manager and Volunteering Lead, Hazel, who advised that they are always keen to hear from people interested in volunteering, particularly anyone who can help out in December in the run up to Christmas, one of the busiest times for them. So, if this has inspired you, check out their website and contact them! And please consider popping something in the foodbank donation boxes next time you’re at the supermarket.

You can find out about our past volunteering days in our previous blog posts:

Food justice and poverty networking event

On 1st May the Bristol Poverty Institute‘s Food and Nutrition Cluster, local charity Feeding Bristol, and the UoB Food Justice Network came together for a workshop exploring how we can collaborate to tackle issues of food justice and poverty. The event kicked off with short presentations from the three hosts, introducing ourselves and our respective work and ambitions. The Director of Feeding Bristol, Ped Asgarian, along with his colleague Jo then provided an overview of the food support landscape in the city of Bristol, sharing some eye-opening stats on levels of deprivation as well as links between poverty and obesity and the impacts of the cost of living on organisations trying to support people who are struggling. They provided details on a range of food support settings that they work with, including food banks, community fridges and school holiday clubs, highlighting the different ways in which people and communities are supported to obtain food in the city. This interestingly intersects with some recent research from one of the BPI’s members, Dr Will Baker, whose work on the rise of food charity in schools has recently generated media attention.

The Feeding Bristol team then went on to outline the challenges that many food support organisations are facing, particularly in terms of funding and resource. This has been driven largely by the rising cost of living, making it more expensive to run the organisations, driving more people to seek help, and also giving everyone less cash in their pockets therefore reducing the amount of charitable donations made. Other contributing factors included the shift away from ‘best before’ dates on some fresh produce in supermarkets, which has meant that food which was previously surplus is no longer available as it remains on the shelves for longer. Even with the best of intentions, it simply isn’t possible to keep some initiatives going. Ped then went on to introduce their Food Equality Strategy and Action Plan, which outlines how they are working with different organisations and embedding and delivering their work on food justice in the city and interacting with national and international work in this space.

Inspired by the opening presentations, we then moved into breakout groups where we explored shared interests and opportunities for collaboration. The focus of the breakout sessions was to establish ways that UoB researchers can effectively collaborate with Feeding Bristol and the wider community. We explored a range of topics in the different groups, including the importance of food education, the role (and duty) the University has to its students who may be facing food poverty, social aspects of food and how food and culture intersect, and the value of listening to different perspectives on what ‘food justice’ means to different people and communities and what the barriers are.

The discussion was really engaging, and could have gone on for much longer, and provided some really great ideas for the focus and format of our next joint event in July coinciding with Feeding Bristol’s annual Food Justice Fortnight. We’re really looking forward to working with our colleagues from the Food Justice Network and Feeding Bristol to develop these plans in the coming weeks. The event has been pencilled in for the afternoon of Thursday 4th July, and we plan to create an open space to share ideas and bring together diverse voices, perspectives and understandings of what ‘food justice’ means and how it can be achieved. Do save the date and keep an eye on the BPI events page for more information in due course, or contact Joe (joe.jezewski@bristol.ac.uk) if you would like to be notified when event registration launches.

UN World Day of Social Justice

The 20th of February 2024 is the 15th UN World Day of Social Justice, a date that seeks to highlight the centrality of social justice as a guiding principle for the actions of States in the construction of fair and cohesive societies at the national, regional, and international levels.

The construction of a “society for all” requires that States, the international community, and all stakeholders – such as academia and civil society – work towards the eradication of poverty and the development of more equitable societies with equal opportunities through the promotion of full employment and decent work, universal access to social welfare, and gender equality, amongst other focus areas/initiatives. Ultimately, it is about pooling efforts towards reducing existing social gaps, promoting integration, and eliminating all forms of structural inequalities. In the words of the former Secretary-General of the UN, Ban Ki-Moon: “The World Day of Social Justice is observed to highlight the power of global solidarity to advance opportunity for all“[1].

For this year’s commemoration, the United Nations has placed emphasis on a challenging global context: the persistence and deepening of injustices such as job insecurity, high levels of inequality, violent conflicts, and ongoing global crises.

For further information, visit: UN Social Justice Day. In addition, visit the International Labour Organisation’s event page and tune in to their live stream.

The Bristol Poverty Institute (BPI)

For the past 25 years, the Bristol Poverty Institute (BPI) and Towsend Centre for International Poverty Research has facilitated multi-disciplinary policy focused research into the eradication of poverty and the pursuit of greater social justice. We have collaborated with United Nations and international organisations, governments, NGOs, charities, and the private sector, united by the common goal of SDG1: to reduce poverty in all its forms everywhere and leave no-one behind.

Our work focuses on a wide range of poverty-relevant issues from various disciplinary perspectives, with strengths and convergence around the themes of child health, education, livelihoods and debt, and food and water, among others.

Our aims are:

- The production of practical policies and solutions for the alleviation and eventual ending of world poverty.

- Greater understanding of both the scientific and subjective measurement of poverty.

- Investigation into the causes of poverty.

- Analysis of the costs and consequences of poverty for individuals, families, communities, and societies.

- Research into theoretical and conceptual issues of definition and perceptions of poverty.

- Wide dissemination of the policy implications of research into poverty.

We are driven by our overarching objective of reducing the extent, scale, and severity of poverty worldwide and advancing social justice in the UK and other countries.

This is why we have joined the United Nations led commemoration this year, as the call for ‘building a society for all’ lies at the heart of our Institute’s work, just as social justice is one of the cross-cutting strategic goals of the University of Bristol.

See more: Bristol Poverty Institute

BPI’s work

Social justice is deeply ingrained in the ethos of our institute, serving as a guiding principle for the diverse range of activities and initiatives we undertake here at the BPI. In our pursuit of multidisciplinary research and vibrant knowledge exchange platforms, we recognize the true significance of such social-justice-driven research and platforms when they actively contribute to the empowerment and transformation of communities.

While it is impossible to encapsulate all our endeavours in the realm of social justice within this space, we are eager to share some of our most impactful contributions to driving positive change and equity in our society. Some examples of our social justice related work are as follows:

- Transforming the definition and measurement of poverty and social exclusion: Our institute has been involved in the development of the ‘consensual method for measuring multidimensional adult and child poverty‘, which measures poverty by assessing direct measures of living standards and identifies deprivation as an enforced lack of socially perceived ‘necessities’. This method is currently used in the UK and in every country in the EU.

- Improving global efforts to reduce child poverty and deprivation: Our approach to assessing child poverty pioneered the creation of the first scientific assessment of the extent and nature of extreme child poverty in the developing world – including access to adequate shelter, safe drinking water and sanitation, education, information, healthcare, and food. UNICEF launched its Global Study on Child Poverty and Disparities in 2008 in 54 countries with over 1.5 billion children where the BPI team supported governments and UNICEF country offices in applying our multi-dimensional approach. Read more on this on our Research Impact page.

- Reducing inequalities in educational attainment: Our research, integral to the Independent Review on Poverty and Life Chances, shaped government strategies from 2010 to 2015, particularly in areas of Social Justice and Child Poverty. It underscored the significance of early childhood education, prompting initiatives to bolster health visitor numbers and expand programs supporting families. Additionally, our findings influenced policies addressing educational disparities among black and minority ethnic learners, resulting in targeted interventions to enhance outcomes.

- Poverty and health inequalities: The University’s pioneering life-course research has profoundly influenced policy and practice, particularly in addressing health inequalities. By revealing the impact of early-life factors on health conditions like stroke and stomach cancer, and highlighting the association between poverty and childhood injuries, our studies have guided targeted interventions to mitigate these effects.

Moreover, our work has shifted the narrative on health inequalities, focusing on the complex mechanisms through which poverty affects health outcomes rather than simply attributing them to individual behaviours. With ongoing research in methodologies like epigenetics, we continue to inform global anti-poverty policies, improving the lives of millions worldwide.

These are just a few examples where our work and research have influenced public policies in areas relating to healthcare, education and childhood poverty; thematic areas that cross-cut the wider thematic areas of poverty and social justice. In addition to these examples, we have many more in areas such as housing and homelessness, access to financial services, and marginalization that we address in our five research clusters.

For more information, visit: Bristol Poverty Institute – Poverty Research Impact

- Support for researchers: As a central part of our work, the BPI is dedicated to fostering a dynamic, inclusive research environment. This commitment is reflected in our provision of a SharePoint site designed to support University of Bristol colleagues collaborating with the Bristol Poverty Institute. This platform offers guidance and resources, including information on BPI’s Research Clusters, internal and external funding opportunities, and links to other useful University resources.

Our five research clusters aim to unite experts from various disciplines across the University to identify synergies, exchange expertise, and pursue collaborative opportunities: Child Health and Development; Education and Inequalities; Food and Nutrition; Livelihoods and Debt; and Multidimensional Poverty Measurement. For more information, visit: Bristol Poverty Institute – Research Clusters (Link for UoB staff only). Aligned with the work of the BPI, members of our board have a prolific background in social justice, linked to each of their areas of expertise.

- Camila Morelli: “Animating the Future” Project. In collaboration with academics from Peru, indigenous researchers, and professional animators, Camila leads the “Animating the Future” Project. This initiative explores the life trajectories of indigenous migrant youth (from rural to urban areas) in various regions of Peru, aiming to preserve the stories and traditions of Amazonian peoples through participatory methods. Participants are encouraged to share their experiences firsthand through visual expression methods. “We found that involving youth actively in documenting traditional cultures through visual methods can be a powerful way to achieve this goal, creating a space where young people who feel unseen can gain a sense of visibility” – C. Morelli. For further information, please visit: Using Animation to Help Young Amazonians Tell Their Story

BPI’s latest social justice related news and activities

- Seedcorn Fund. We are pleased to announce our latest internal funding opportunity is now open! This fund is designed to support and catalyse poverty-relevant research at the University of Bristol (UoB), providing a pipeline from our activities to larger funding bids. Interdisciplinarity and social justice will be key aspects of all successful bids and UoB academics will be able to apply for awards between £3000-£6000. We anticipate funding 2-3 projects in the 2023-24 academic year. There will be further funding available in 2024-25, with more information available in due course. For the current round of funding, applications will be reviewed on a rolling basis until all funds have been allocated or the final submission deadline, 1 May 2024, has been reached, whichever is sooner. For further information, please visit: Seedcorn Funding Scheme

- Upcoming BPI Conference 2024. Poverty and Social Justice in a Post-COVID World (5-6 June 2024). The conference will focus on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on various dimensions of poverty and the challenges societies face in a post-COVID world. The first day, held in person, will address the gaps and challenges in the UK – related to themes such as health, education, employment, livelihoods, debt, and structural inequalities – through interdisciplinary and cross-sector panels. The second day, conducted online, will analyse international post-COVID recovery through regional panels covering Asia and Oceania, Europe and Africa, and the Americas.

For further information, please visit: BPI Conference 2024

—————————

[1] Ban Ki-Moon, former Secretary-general of United Nations Message on the World Day of Social Justice 2014 on https://news.un.org/en/story/2014/02/462202-world-day-social-justice-un-urges-action-end-poverty-overcome-inequality. (Last seen 13.02.2024).

BPI 2023 wrap-up blog post

As we welcome in 2024, the BPI team are reflecting on the challenges, successes and opportunities we have experienced through 2023, and looking ahead to the coming year and beyond. Join us for a whistle stop tour of a few of the highlights in this blog post! If you want to keep up to date on activities and opportunities across the Institute, do make sure you sign up to our monthly newsletter via this page and/or email the BPI team to sign up to our main mailing list.

January

In January 2023, the BPI’s main focus was on producing and submitting a bid to the internal Strategic Research Investment Fund (SRIF). With input from the BPI Advisory Board, the BPI Manager Dr Lauren Winch put together a strong bid with a number of work packages, and we were delighted when funding for all work packages was confirmed in March. Funding has been secured for a range of activities up to July 2025, which includes new posts within the team, an exciting new interdisciplinary seedcorn fund, and a BPI conference in 2024.

February

On 12th February we were delighted to welcome Dr Nkechi S.Owoo to Bristol as a Bristol ‘Next Generation’ Visiting Researcher. Dr Nkechi, a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Economics at the University of Ghana, spent six weeks working with the BPI Director, Professor David Gordon on the effects of climate change on health outcomes. Nkechi is one of Africa’s foremost young scholars, and her research focuses on spatial econometrics in addition to microeconomic issues in developing countries, including household behaviour, health, poverty and inequality, gender issues, population and demographic economics, as well as environmental sustainability.

March

Some of our activities in the first part of the year were significantly impacted by strike action across the University sector. This included plans for a cross-sector event on Housing, ‘Home’ and Poverty scheduled for 15th March, which had to be postponed until May. We did, however, deliver a fantastic event in collaboration with the South West International Development Network (SWIDN) to celebrate International Women’s Day on the 8th March, chaired and facilitated by BPI Board Member Dr Tigist Grieve. At this collaborative online event entitled ‘From Menarche to Menopause‘ we heard from several expert speakers from the academic and not-for-profit communities about their work and research related to menarche, menstruation, menopause and mental health worldwide. Together the event explored issues affecting women and girls and discussed what we can do as a wider community to tackle these issues. More information is available on the event page.

Dr Nkechi Owoo also continued her work with the BPI in March, before returning home to Ghana. This included an engaging hybrid seminar on ‘The Effects of Climate Change on Health Outcomes in Ghana’. A recording of the seminar along with more information is available in the events resources section of our website.

March was a particularly busy month for the BPI Director, Professor David Gordon, who travelled to Sweden after Nkechi’s departure to work on an evaluation of the AgeCap programme in Sweden, and then chaired an all-day meeting for the Academy of Finland the following week.

April

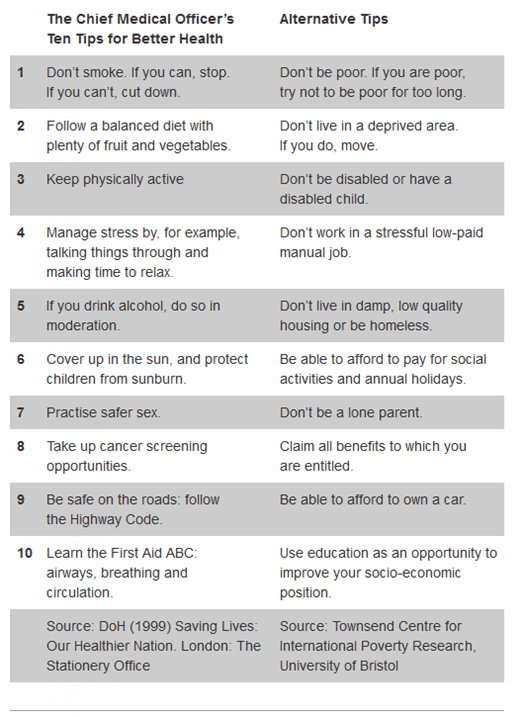

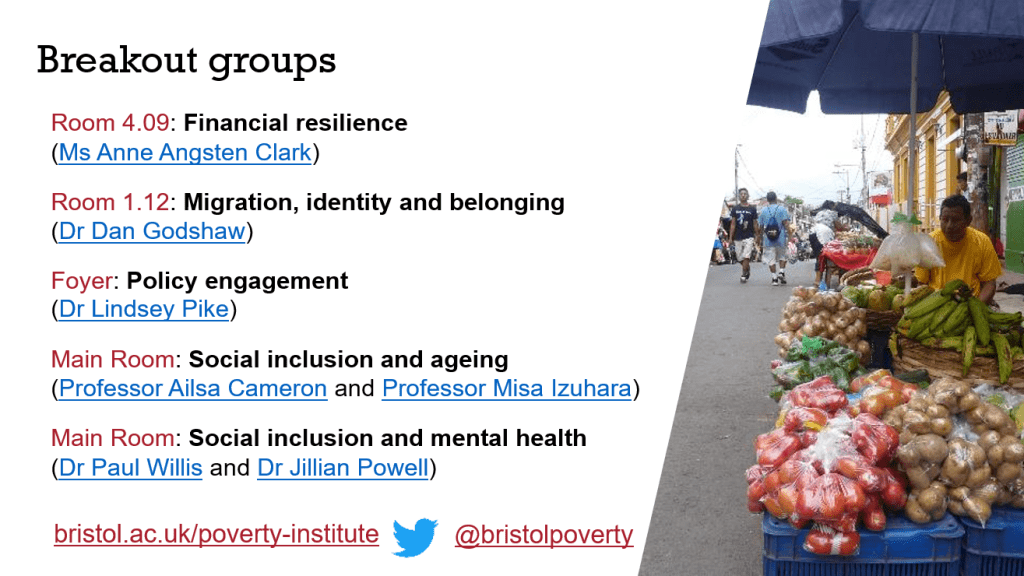

In April, we teamed up with the University of Bristol’s Health Psychology and Interventions Group (HPIG) for an afternoon of thought-provoking discussion at a cross-sector workshop. Entitled “Don’t Be Poor”: Collaborative approaches to health behaviour change interventions, this workshop was aimed at those wishing to explore the real-world context of health interventions and how we can better bring together our skills and collaborate across disciplines when designing interventions and conducting healthcare research to bring tangible benefits to those most in need. We were really pleased that the event attracted a wide range of attendees from across different sectors, with some really positive takeaways including an enhanced awareness and understanding of dimensions of poverty and vulnerability which can intersect with health behaviours.

The title of this event was inspired by some work undertaken by Professor David Gordon and colleagues over twenty years ago. This was inspired by some ‘top tips’ for better health from the Chief Medical Officer as part of the Government’s published response to the Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health report. These ‘top tips’, whilst valid in themselves, neglected to really address the causes or potential solutions to health inequalities. This therefore prompted a somewhat satirical response from Professor Gordon and his colleagues which highlighted the kinds of policies which would be needed to actually reduce health inequalities in the UK. One of their key ‘tips’ for better health was simply: “Don’t be poor”. It seems these lessons may still need to be learnt.

May

May was another really busy month for the BPI, with a range of events and high-level meetings. This included, for example, successfully delivering our half-day multi-sector event on Housing, ‘Home’ and Poverty, feeding into the new GW4 strategy, meeting with members of the Global Coalition to End Child Poverty to outline collaborative work on climate change and child poverty, and convening a meeting for the Directors of all seven of the University of Bristol’s Specialist Research Institutes.

The Housing, ‘Home’ and Poverty event was a real highlight, bringing together representatives from different sectors and backgrounds to explore the intersections between poverty and elements of housing, the concept of ‘home’, and other related issues. The event included presentations, breakout sessions, a powerful testimony on the experience of these issues in conjunction with living with disabilities, and networking opportunities. Presentations from the event can be downloaded from our event resources page, and you can also find out more about the event itself in our blog post.

June

In June we welcomed Dr Tanveer Naveed from the University of Gujrat in Pakistan who also came to Bristol via a Bristol ‘Next Generation’ Visiting Researcher award, the same scheme which funded Nkechi’s visit earlier in the year. Tanveer’s research interests and contributions focus on measuring valid and reliable education, assets, health and human development indices, and developing scientifically rigorous measures for multidimensional poverty and child poverty that are applicable in low- and middle-income countries. During his visit, Tanveer collaborated with the Professor David Gordon on multidimensional poverty measurement, particularly in Pakistan.

June also saw the publication of a fantastic new book on Decolonizing Education for Sustainable Futures from BPI Advisory Board Member Professor Leon Tikly, along with Bristol academics Dr Artemio Cortez Ochoa, Professor Julia Paulson and Warwick’s Professor Yvette Hutchison. This book explores the link between sustainable futures and decolonized education, offering theoretical and practical insights on creating decolonized futures through innovative approaches and reparative justice in education.

July

Our visiting researcher from University of Gujrat, Dr Tanveer Naveed, gave two fantastic seminars in July. The first was on The Construction of Household-based Asset Index: Measurement of Economic Disparities in Pakistan by using MICS Micro-data, and the second on The Estimation of Human Development Index at Household Level and Estimation of Human Development Disparities in Pakistan. Resources from both seminars can be found on the BPI website.

We also had some changes in the BPI team in July. We bid farewell to our long-standing Senior Administrator Joe Gillett, who was moving on to undertake some research of his own building on his PhD research. We also said goodbye to Katherine Fitzpatrick, who had come in on a fixed-term contract to help us out with some packages of work. Both will be very missed from the team, but we were delighted to welcome Tracey Jarvis as our new permanent Senior Administrator taking over from Joe. Tracey got up to speed really quickly, and has been a fantastic asset to the team.

August

August is always a quieter month in terms of events and meetings, as many people take a break over the summer. It was still a busy month for the BPI team, though, developing plans for the upcoming autumn term and launching recruitment for our new BPI Development Associate who will lead on our new Seedcorn Fund in 2024.

September

September saw a wave of high-profile events for the BPI in collaboration with colleagues including UNICEF and the New School in the USA. Our largest activity was a side event at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Science Summit, hosted at UNICEF’s Head Office in New York on the topic of Advanced Tools for Analysing Poverty, Climate and Environmental Changes. Chaired and co-designed by the BPI Director, Professor David Gordon, this event brought together researchers engaged in novel approaches to develop measures, monitoring, and understanding for both the causes and the consequences of poverty. Despite many decades of progress, hundreds of millions of people still live in extreme poverty. Consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, economic and political turmoil, armed conflicts, and environmental challenges do not only threaten to halt recent improvements but reverse many of the gains in poverty reduction. Whilst numbers in the room were limited, the session attracted hundreds of attendees from all around the world on the live stream.

Following on from this, we were also involved in a parallel event hosted by the New School on Improving Child and Family Poverty Measurement which brought together some of the world’s leading researchers into poverty and deprivation measurement and anti-poverty policies who had travelled to New York for the UNGA Science Summit.

October

October saw the new academic year getting into full swing, and we held a really nice, informal ‘Meet the BPI’ event on campus. The aim of the event was to give both academics and Professional Services colleagues from our University the opportunity to meet the BPI team, find out what we do, learn more about the support and engagement opportunities available through the BPI, and mingle with like-minded colleagues over a cuppa. We had a really good turn out, and it was a great opportunity to catch-up with familiar faces and meet some new ones and identify some potential new synergies and spaces for engagement and collaboration.

The 17th October every year is the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty (IDEP), and each year the Global Coalition to End Child Poverty – which we are an active member of – plan activities to coincide with this. Last year we published a policy briefing on Ending Child Poverty: A Policy Agenda, and this year we launched a Call to Action for Governments to expand social protection and care systems and promote decent work to address child poverty. This Call to Action was developed jointly by UNICEF, Save the Children, Young Lives, Arigatou and the Bristol Poverty Institute, and was officially launched at a live online event on IDEP itself. Find out more in our news story.

November

November was our busiest month of the year for events, with a packed schedule including a hybrid seminar, a co-hosted conference session, and an interdisciplinary forum. We kicked off the month with our hybrid event exploring Towards Net Zero and Tackling Poverty, where we introduced findings from our Travel Carbon Project which was undertaken by Professor David Gordon and one of his PhD students who is already a qualified medical doctor, Dr Cynthia Fonta. Their aim was to calculate both the costs and years of life which could be saved by carbon offsetting the University’s work-related emissions through funding clean cooking stoves and/or potable water provision in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. They shared their findings and the potential implications with a hybrid audience at this event, alongside an engaging presentation from Dr Sam Williamson, who is doing work on sustainability and cooking in a range of contexts including Nepal, Sierra Leone and Uganda.

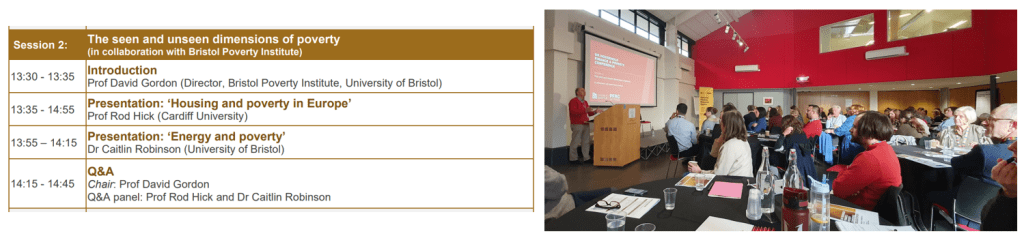

The following week, we co-hosted a session on The Seen and Unseen Dimensions of Poverty at the fantastic Personal Finance Research Centre (PFRC) anniversary conference. This well-organised and well-attended event was celebrating 25 years of the PFRC, which applies multi-method approaches with specialisms drawn from social policy, human geography, psychology, and social research to explore the financial issues that affect individuals and households under the leadership of BPI Board Member Professor Sharon Collard.

A final highlight was our interdisciplinary forum on Poverty and Social Justice in a Digital Future, which consisted of two thematic sessions exploring digital inequalities and the impacts of AI on poverty. The aim of this event was to build up internal awareness and offer researchers from different communities to identify synergies, with a view to being better placed to collaborate in response to future funding calls and to situate considerations of poverty and social justice within the mindsets of researchers working in the digital space for these future bids. We actively encouraged participation from researchers who weren’t currently working directly on poverty or poverty-related issues, and from all corners of the University. We had a fantastic panel of speakers from across Arts, Social Sciences, and Engineering, who gave us wide-ranging, engaging talks on new frontiers of colonialism and marginalisation, discrimination and disinformation, participatory research methods, sociodigital futures and social justice, cyber security, and machine learning and AI.

December

As 2023 drew to a close, there were lots of exciting things still happening at the BPI. We were delighted to welcome Joe Jezewski to join our team as our new BPI Development Associate, as well as four new academics to our BPI Advisory Board bringing more diversity and expertise to our already strong Advisory Board. Our new Board members are:

- Dr Camilla Morelli, Lecturer in Social Anthropology

- Professor Julie Mytton, Honorary Professor in Bristol Medical School

- Professor Tonia Novitz, Professor of Labour Law

- Dr Caitlin Robinson, Research Fellow and Proleptic Lecturer in Geographical Sciences

In other news, the BPI Director travelled to Thailand to work with the Thai government and UNICEF on poverty measurement for the country. Closer to home, members of the BPI team rolled up their sleeves to bake cakes and cookies to raise money for the North Bristol and South Gloucestershire foodbank, where some of the BPI team and colleagues spent a rewarding day volunteering on 21st December. You can find out more about our experience, including some information about the foodbank and tips for donating, in our blog post.

Looking ahead

So, it has been another busy year for the BPI, and we’re really excited to have lots of exciting things in the pipeline, including our new interdisciplinary seedcorn fund launching imminently, collaborations with a range of local, national and international partners, and a wide range of events. We’ve got our rescheduled event on gambling, poverty and marginalisation, as well as new events in development including a seminar on underemployment and Universal Credit, a participatory research methods workshop, training on achieving impact for poverty-relevant research, a seminar on socially just future cities, a food justice mingle, to name just some of them! Of course, we will also have our 2024 conference! This will be taking place across two days in June, with a focus on Poverty and Social Justice in a Post-COVID World. The first day will be an in-person event in Bristol with a UK focus, and the second day will be online with an international audience and focus. We’re aiming to have sessions across a wide range of topics including mental health, finance, and education among others, and will try and make sure there are sessions available to people in different time zones around the world. We’ve just recruited a new member of our team to help with planning and delivery of this conference, who will be joining us later this month – more info soon!

To keep up to date with the BPI’s plans you can sign up to our mailing list, subscribe to our monthly newsletter, check out our website, and/or follow us X/Twitter. You can also get in touch with the BPI team via bristol-poverty-institute@bristol.ac.uk– we’d love to hear from you!