Introduction

As we welcome in 2023, the BPI team are reflecting on the challenges, successes and opportunities we have experienced through 2022, and looking ahead to 2023. Join us for a whistle stop tour of a few of the highlights in this blog post!

January

In January we launched our new BPI research page, where you can search and browse a wide range of poverty-relevant projects, publications and researchers at the University of Bristol. This was one of the final projects delivered by our Communications Officer, Sasha, who left the BPI at the end of January to pursue her career as a Barrister. We wish her all the best in her new career.

The BPI Director and Manager also met with the Chief Officer of Bristol Disability Equality Forum, Laura Welti, to discuss opportunities for collaboration, as well as plans for an upcoming event on the disproportionate impacts of the pandemic on disabled people.

February

The Disability, Poverty and COVID-19 webinar had been planned for February; however, due to successive periods of strike action at the University this was postponed several times.

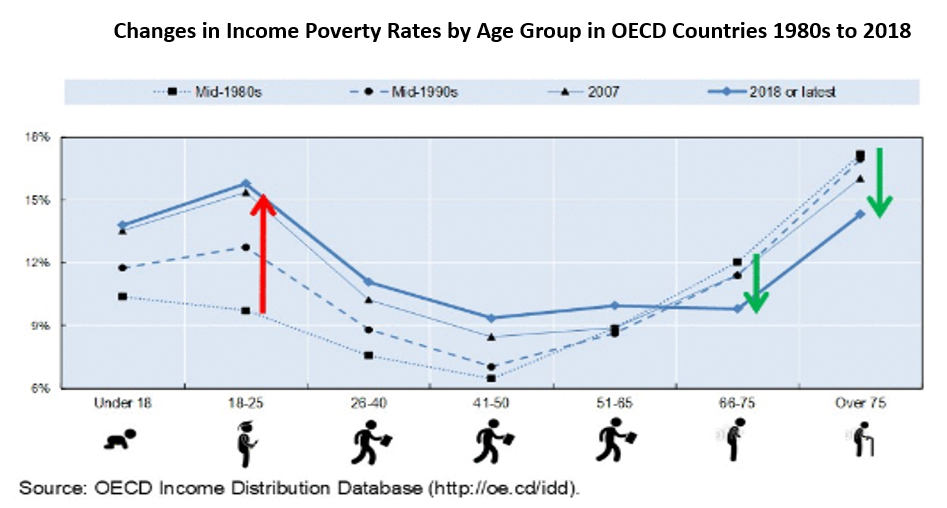

In between the strike periods, the BPI Director, Professor David Gordon, ran an online multi-source inference session for the Deep Statistics: AI and Earth Observations for Sustainable Development programme at the Department of Statistics at Harvard University on behalf of the BPI. We also successfully secured some internal funding for a project on Improving the global measurement of child and family poverty in collaboration with UNICEF. The aim of this initiative is to develop and pilot a short question module which will use the Consensual Approach to produce accurate, precise and comparable measures of multidimensional poverty for children and their families. After piloting the questionnaire, it could be applied in all countries of the world.

March

March saw further strike action, impacting on our plans for events. However, despite this it was a really productive month for the BPI. A key highlight was when BPI Board Member Professor Sharon Collard, in collaboration with Professor Agnes Nairn, were awarded £4m from GambleAware for a new Bristol Hub for Gambling Harms Research at the University. This bid built on discussions at a BPI webinar we ran in partnership with GambleAware in 2020 which both Sharon and Agnes presented at, and the BPI was listed as an associated Institute on the bid which included a formal letter of support from the BPI.

We also met with the charity National Energy Action (NEA) to discuss spaces for collaboration on tackling fuel poverty, as well as colleagues in the Centre for Academic Child Health. We are looking forward to progressing these discussions further in 2023, and some funding has recently been awarded to Dr Caitlin Robinson in Geographical Sciences to work with NEA and BPI on the challenges of fuel poverty.

April

In April we were pleased to relaunch our BPI Internal Research and Collaboration Fund, which is still open for applications until 31 May 2023 or when all available funding has been allocated, whichever is sooner. The funding scheme supports small-scale activities to grow and develop the University of Bristol poverty-research community and its visibility. Activities are likely to include seminars and workshops, and in this relaunch we have opened the scheme up to include virtual activities as well as in-person activities, recognising the fact that ways of working have changed, and the lower environmental impact of virtual engagement.

May

May was another really busy month for the BPI, with a range of events and high-level meetings. This included, for example, a joint grant development workshop with our colleagues from Migration Mobilities Bristol (MMB) and members of the Research Development team in Professional Services where attendees were provided with tips for applying to the research councils for funding. We also met with members of the University of Cape Town, including their Vice Chancellor and their Director of Global Engagement, to discuss institutional collaborations at the nexus of climate change, health and poverty along with the Directors of our University’s environment and health research Institutes. A further highlight in May was a Data Collection webinar which the BPI organised for UNICEF Headquarters on Child and Family Poverty Measurement.

June

Our focus in June was on our BPI Showcase event at the end of the month, which was our first in-person event since the pandemic. This half-day event brought together friends, colleagues and associates from a range of organisations to showcase, celebrate and explore poverty-relevant research at the University of Bristol and beyond. We explored a range of topics including global poverty, the cost-of-living-crisis, decolonising development, multidimensional poverty, (il)licit livelihoods and drugs policies, and social, digital and cultural lives of minoritized older adults. The event also highlighted research taking place in a wide range of geographical contexts, from local analyses in Bristol to projects in Somali/Somaliland and Bangladesh, a wider project across several African countries, and poverty on a global scale. The delegate pack – including speaker biographies and talk abstracts – is available on the BPI website, along with slide decks from the presentations and pdfs of the posters displayed at the Showcase, and a summary of the day is available on the BPI blog.

July

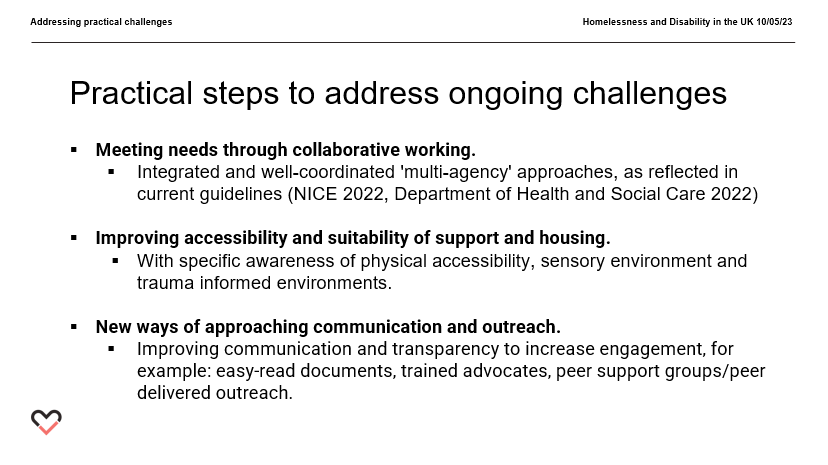

In July we finally (!) held our webinar on Disability, Poverty and COVID-19, which had been postponed and rescheduled several times due to University strike action. Over 150 people registered for this event including representatives from Pfizer, Bristol City Council and a range of other city and county councils, Deliveroo, various parts of the NHS, Bristol Museums, Citizen’s Advice, Barnardo’s, and the West of England Centre for Inclusive Living, alongside academics from multiple universities. We were delighted to be joined by speakers from a range of organisations and sectors, including some with lived experience of disability.

A further highlight from July was news of the appointment of then-BPI Board Member Professor Esther Dermott to the role of Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences and Law at the University of Bristol. Whilst this was fantastic and well-deserved news, it does unfortunately mean that from 2023 Esther will be stepping down from her role on the BPI Board. We would therefore like to take this opportunity once again to thank her for all of her fantastic contributions to the BPI over the years.

August

August brought our first international trip since travel opened up again, with the BPI Director and Manager travelling to South Africa to deliver a week-long advanced poverty methods training course at University of Cape Town (UCT). The BPI Director, Professor David Gordon, travelled out earlier in the month to undertake some collaborative work with colleagues at the University of Stellenbosch, before heading to Cape Town to meet up with BPI Manager Dr Lauren Winch as well as Professor Rich Harris from Geographical Sciences for the training course. The hybrid course included sessions on Global Policy Analysis, Spatial Analyses and Universal Poverty Measurement, delivered by a range of world-leading experts. The BPI Manager additionally gave a well-attended session on partnership opportunities as well as meeting with UCT’s Vice Chancellor Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng to strengthen collaborations between University of Bristol and University of Cape Town staff and students.

Whilst we were in South Africa we also received news of the timely publication of a paper on Inequalities in COVID-19 vulnerability in South Africa which was co-authored by BPI and UCT researchers.

September

In September the BPI team were really excited to launch our new monthly newsletter, which shares poverty-relevant news, events, funding opportunities and links to resources. All issues so far are available via the BPI website, and you can subscribe to future issues via this link. Another highlight was a really productive virtual meeting with representatives from Save the Children International around the world to explore spaces for collaboration on climate change and child poverty. We followed up on these discussions at the annual meeting of the Global Coalition to End Child Poverty in December (see below) and are in the process of scheduling a follow-up meeting with members of their Asia-Pacific team early in 2023.

We were also delighted to hear that BPI Board Member Professor Leon Tikly was one of two University of Bristol academics conferred as a Fellow of Academy of Social Sciences in September.

October

The 17th of October is the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty. This year saw the publication of a policy briefing on Ending Child Poverty: A Policy Agenda to mark the occasion, co-authored by representatives of the BPI alongside some of the world’s leading anti-poverty organisations. Elsewhere, BPI Board Member Dr Tigist Grieve represented the BPI at the South West International Development Network (SWIDN) conference 2022, running a well-attended session on development and poverty. In October we were also really pleased to welcome Professor Yoav Ben-Shlomo as an official member of the BPI Advisory Board, replacing former members Dr Matthew Ellis and Professor Alan Emond as our health representative after they both retired last year. We want to take this opportunity once again to thank them for their fantastic contributions to the BPI over the years, and to thank Yoav for coming on board. We also welcomed a new part-time Administrator, Katherine Fitzpatrick, to the BPI team. Katherine will be working one day per week until July 2023 alongside our existing part-time Administrator Joe Gillett.

November

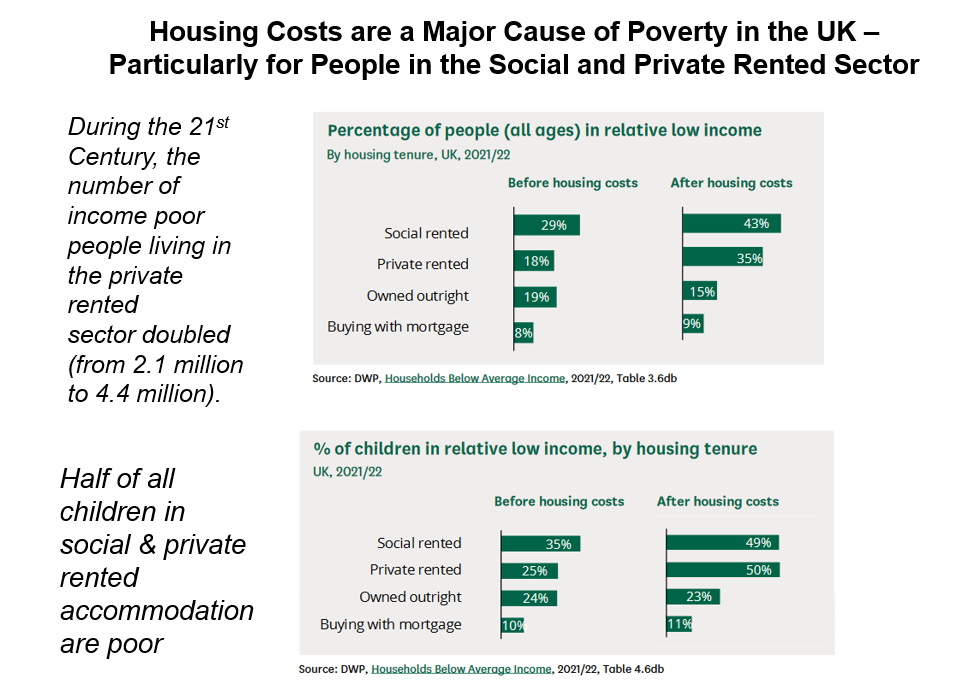

In November the BPI Director was invited to give a talk on in-work poverty and low pay at Bristol City Council’s ‘Living Wage Week’. With the ever-changing political landscape and developing cost-of-living crisis this was a challenging presentation to prepare for, as the situation was changing almost daily. The presentation was very well received, however, with some thought-provoking reflections and shocking statistics. We also received fantastic news in November that our applications for two Bristol ‘Next Generation’ Visiting Researcher awards to bring future research leaders from Ghana and Pakistan to work with the BPI Director and engage with the broader BPI and UoB community were successful. These are:

- Dr Nkechi Owoo, a Health and Demographic Economist at the University of Ghana who will be visiting Bristol for six weeks in Spring 2023 to work with us on the effects of climate change on health outcomes.

- Dr Tanveer Naveed, a Development Economist at the University of Gujrat who will be visiting Bristol in June 2023 for two weeks to work with us on multidimensional child poverty in Pakistan.

November also saw the BPI Director and Professor Paul Bates (Geographical Sciences) give a presentation about who is most vulnerable to climate change in Pakistan to UNICEF and UN Agency staff during COP27, as a pro bono contribution to the massive 2022 flood post disaster needs assessment planning.

December

As 2022 drew to a close, things remained busy for the BPI team. At the start of the month the BPI Director and Manager travelled to London to join the annual meeting of the Global Coalition to End Child Poverty, where representatives from leading anti-poverty organisations around the world came together to reflect on our work in 2022 and develop our work plan for 2023 and beyond. The Global Coalition to End Child Poverty is a global initiative to raise awareness about children living in poverty across the world and support global and national action to alleviate it. Coalition members work together as part of the Coalition, as well as individually, to achieve a world where all children grow up free from poverty, deprivation and exclusion. In 2020 the Bristol Poverty Institute (BPI) were honoured to accept an invitation to join the Coalition, which is co-chaired by UNICEF and Save the Children with 19 other leading organisations in tackling poverty from around the world.

You can find out more about the Coalition and the meeting on our blog post.

Whilst the BPI Director stayed in London after the meeting to continue the discussions, the BPI Manager hopped on a train back to Bristol so she could attend the University of Bristol’s ‘Is a just transition to Net Zero possible & what does it look like’ event the following morning. This was a really engaging event, and building on conversations at the event we are now exploring some collaborative work with Cabot Institute for the Environment and the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute for Health Research on carbon offsetting and potential benefits for health and wellbeing. We are really excited to see where these conversations take us in 2023!

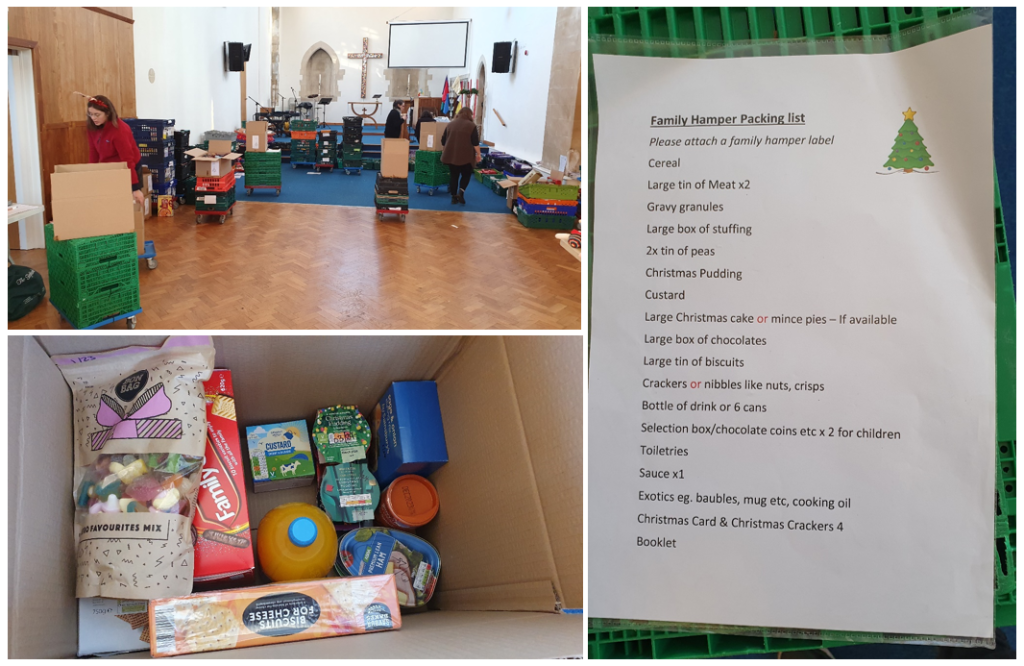

Finally, we wrapped the year up with our now yearly tradition of helping out at a local foodbank. This year we were able to send 24 members of the University – including both academics and members of Professional Services – to the Northwest Bristol foodbank to help out over three separate days. You can find out more on our blog post.

Looking ahead

Phew! 2022 really was a busy year and we hope you have enjoyed sharing some of our highlights with us.

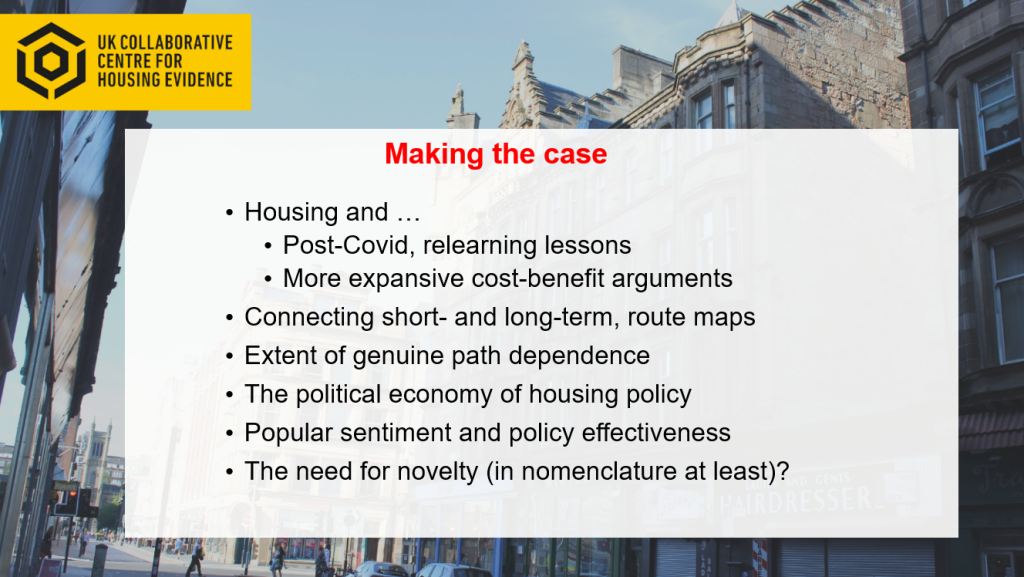

Looking ahead we have several exciting things under development, including an event on Housing, ‘Home’ and Poverty in March, and a collaborative workshop on health and poverty entitled Don’t be Poor: Collaborative approaches to health behaviour change interventions in April. We will also be meeting with representatives from Bristol City Council’s public health and communities team to explore opportunities for collaboration, developing our Research Clusters, exploring opportunities for further training courses, and planning for our next conference, among other activities. To keep up to date with the BPI’s plans you can sign up to our mailing list, subscribe to our monthly newsletter, check out our website, and/or follow us on Twitter. You can also get in touch with the BPI team via bristol-poverty-institute@bristol.ac.uk – we’d love to hear from you!

There’s no denying that we’re living in challenging times, particularly for those in and at risk of falling into poverty. It is our mission to tackle poverty in all its forms everywhere, which we will continue to do with vigour in the coming year and beyond.