On Monday the 5th December members of the Global Coalition to End Child Poverty from around the world came together to reflect on our work in 2022 and develop our work plan for 2023 and beyond. The Global Coalition to End Child Poverty is a global initiative to raise awareness about children living in poverty across the world and support global and national action to alleviate it. Coalition members work together as part of the Coalition, as well as individually, to achieve a world where all children grow up free from poverty, deprivation and exclusion. In 2020 the Bristol Poverty Institute (BPI) were honoured to accept an invitation to join the Coalition, which is co-chaired by UNICEF and Save the Children with 19 other leading organisations in tackling poverty from around the world.

Having joined the Coalition in early 2020 this was therefore the BPI’s first in-person meeting with our partners from the Coalition due to COVID restrictions in previous years, and we were really excited to finally meet face-to-face and have those more nuanced discussions and informal chats over coffee which online meetings don’t really allow. It was a long day of meetings – from 8:30am to 5:30pm – but it genuinely didn’t feel like it, and that’s a real testament to both the organisers for a well-planned programme, and also all of the participants for keeping the discussion engaging and for sharing so much interesting information as well as ideas for future research and advocacy activities. In the room we had representatives from All Together in Dignity (ATD) Fourth World, Chronic Poverty Advisory Network (CPAN), Institute for Development Studies (IDS), Nutrition International, Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), Social Policy Research Institute (SPRI), Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), Save the Children and UNICEF, as well as the BPI’s own Director (Professor David Gordon) and Manager (Dr Lauren Winch). We were also joined online by colleagues from Coalition members Arigatou International, African Child Policy Forum, ChildFund International, Eurochild, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Partnership for Economic Policy (PEP), and World Vision.

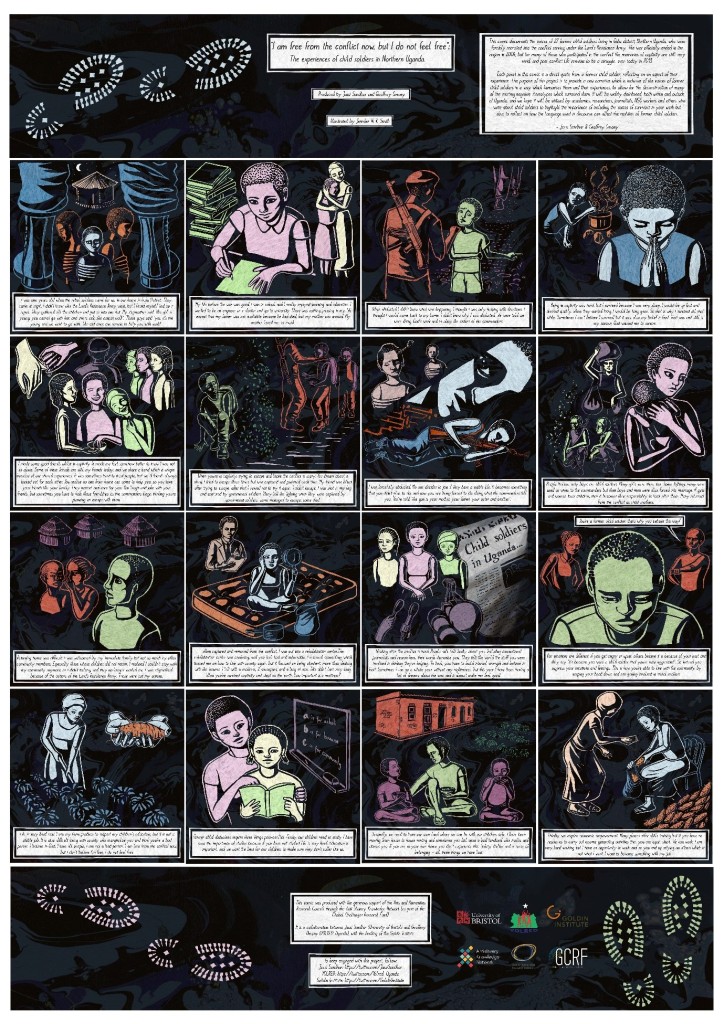

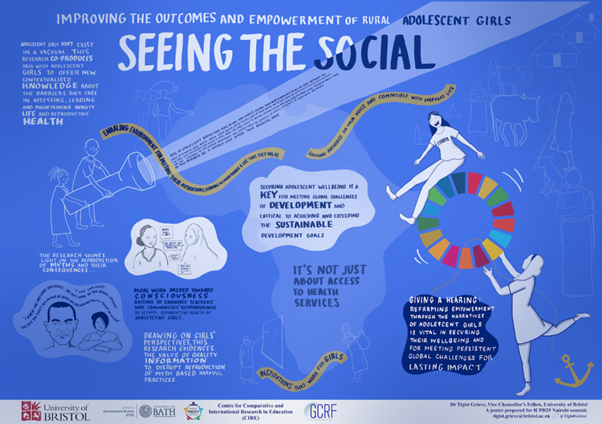

We began by taking stock of members’ activities in 2022, with a key highlight being the publication of a report on Ending Child Poverty: A Policy Agenda, co-authored by representatives from several of the Coalition partners including the BPI. This report was launched on 17 October as part of a wider package of Coalition activities on the annual International Day for the Eradication of Poverty (IDEP) led by ATD Fourth World. A range of other resources and information was also shared as part of this activity, including some ‘myth cards’ based on previous work done by the BPI Director and colleagues. Coalition members also reported a range of other fantastic activities over the course of the year, including online training on understanding child poverty from PEP, Save the Children’s regional event on social protection in Africa, and work on a Multidimensional Poverty Measurement index from OPHI.

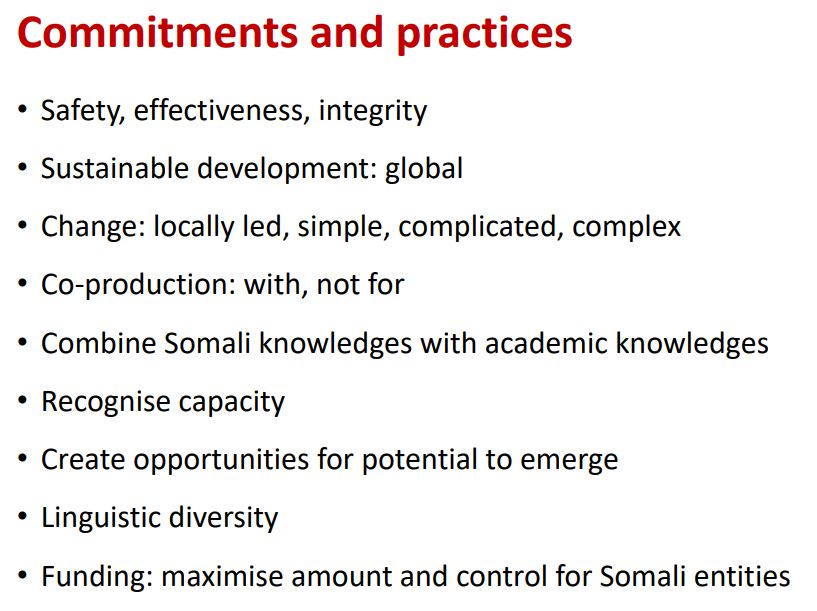

The rest of the morning was dedicated to presentations and the discussions they inspired in the room. The presentations were:

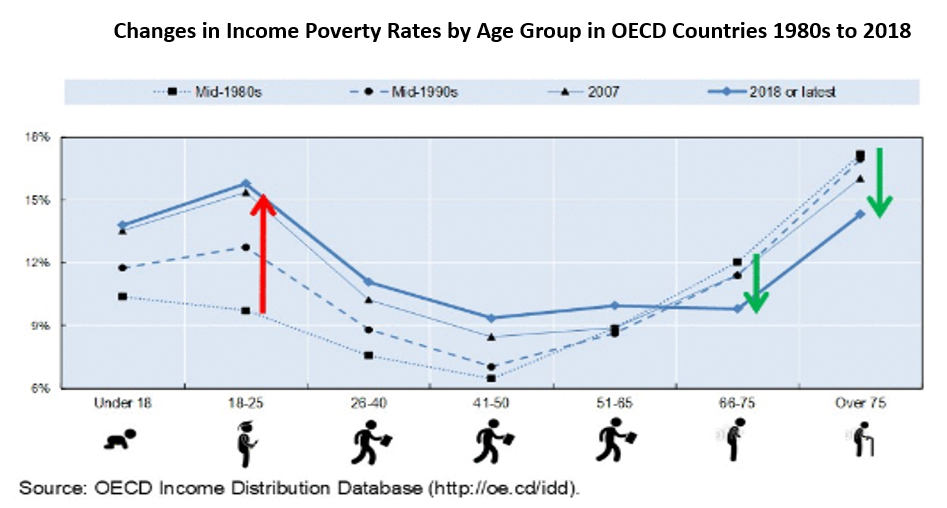

- The state of child poverty, Professor David Gordon (Bristol Poverty Institute)

- Post-covid world: key child poverty themes, Dr Vidya Diwakar and Dr Keetie Roelen (IDS)

These presentations really got the room talking, particularly some of the statistics and evidence shared on child and youth poverty.

This naturally led on to discussions about what we as a Coalition can do to address these challenges, and what our focus should be for 2023. We explored a range of areas of synergy and identified several key priority areas, which will be announced in due course via the Coalition’s communication channels. Some key areas of interest are around the intersections of climate change and poverty – which the BPI are already in active discussion with Coalition partner Save the Children about – as well as resilience at different levels, links between crisis and social protection, the barriers to effecting policy change, stunting as a manifestation of poverty in children, the potential impacts of universal child benefits, and the importance of good political economy analysis. We will also be working together for the next IDEP in October 2023, and the BPI team have offered the Coalition a session at their next international conference which is tentatively scheduled for autumn 2023. A co-authored Handbook on Child Poverty is also currently in draft, with contributions from several Coalition partners. There are therefore a range of exciting plans in motion, and we are really looking forward to seeing how these develop and how the BPI can contribute in the coming year.

We therefore want to extend our thanks again to UNICEF and Save the Children for co-chairing not only this fantastic annual meeting, but for coordinating the coalition throughout the year. Thanks also to Save the Children’s UK office for hosting us in your lovely meeting room, and to all of the collaborators who made the meeting so engaging and productive, and for their work throughout the year. Hopefully together we can make a difference!

To find out more about the Global Coalition check out the links below

- Website: http://www.endchildhoodpoverty.org/

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/globalcoalition

- Newsletters and blogs: http://www.endchildhoodpoverty.org/child-poverty-news-blogs