Tackling the ‘poverty premium’ is a key hurdle to the reduction of poverty in the UK. Indeed, our research at the Personal Finance Research Centre found in 2017 that the average low-income household pays £490 more per year – just because they are poor. While much of this relates to the energy market (for example, being on a pre-payment meter or not being on the best tariff) or the use of high-cost credit, a component that shouldn’t be overlooked is the fact that low-income households often pay more to access cash.

While, in 2019, cash may seem like a thing of the past, we know that many people still depend on it. According to the Financial Conduct Authority (2018), an estimated 2.2 million people report that they only use cash, while UK Finance say that there are 1.3 million who are ‘unbanked’. In our research, we often encounter those who find it difficult to access mainstream banking products, those who find it easier to manage a tight budget in cash, and those who simply lack trust in digital banking. Many of these people are in potentially vulnerable situations; for example, having a disability or a mental health problem.

Given the number of people for whom cash is still king, it’s important that we understand the geography of access to cash and how it is changing over time. In May we therefore published a case study of Bristol, looking at changes in its cash infrastructure between October 2018 and March 2019. Over this period, demand for cash continued to decline and there was a drop in the interchange fees paid by banks when a customer withdraws cash from another company’s ATM, which reduced the revenue of ATM operators.

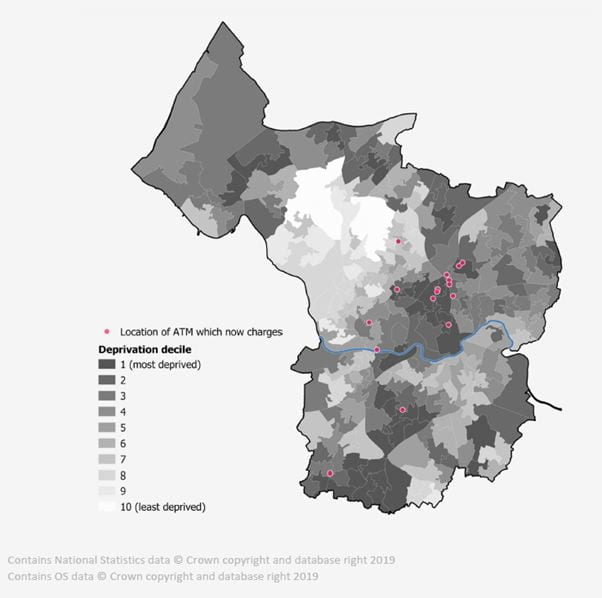

While we found that most of Bristol – and in particular local economic centres – were relatively well-served in terms of access to cash, we noticed that a considerable number of the city’s ATMs had changed from free to fee-charging during this period. More worrying in terms of the poverty premium, was that most of these ATMs were located in the city’s most deprived neighbourhoods – most likely caused by the fact that non-bank ATM operators seem to be dominant in such areas (since banks have largely retreated from such areas towards economic centres).

Location of ATMs in Bristol that changed from free to fee-charging between October 2018 and March 2019. Deprived areas appear disproportionately affected by these changes.

Our research focused only on the city of Bristol and we were therefore pleased that colleagues at Which? published analysis of a national dataset of ATMs in September 2019, looking at differences between January 2018 and May 2019. This confirmed that our findings applied nationally, showing that the 20% most deprived areas had seen 979 (net) conversions from free-to-use to fee-charging, compared with just 223 in the 20% least deprived areas. This is concerning as it risks increasing the poverty premium for those least able to afford it and many of those most likely to depend on cash.

Having identified the problem, however, the challenge now is to identify a solution. We are supporting organisations such as the Payment Systems Regulator, LINK and the Financial Conduct Authority to explore options and are also conducting further research which will consider new ways of identifying areas most in need of cash infrastructure, in rural as well as urban contexts.

The full report is available here.

Authors: Jamie Evans (Senior Research Associate, Personal Finance Research Centre (PFRC), University of Bristol), Sara Davies (Senior Research Fellow, PFRC) and Daniel Tischer (Lecturer in Management, University of Bristol).